Breton Folklore: mythical creatures, witchcraft & old Celtic legends of Brittany

This article gives great authentic & obscure details for writers & storytellers in multiple fantasy & horror genres.

Celtic folklore covers a number of regions - most often, people recognise Scotland, Ireland and Wales.

But much less discussed is the local lore of the Isle of Man or the specific areas of Cornwall (a county in Southwest England) and Brittany (a region of France).

And yet, while these places have a lot of shared cultural detail with those more famous Celtic countries, they also have their own unique elements of lore.

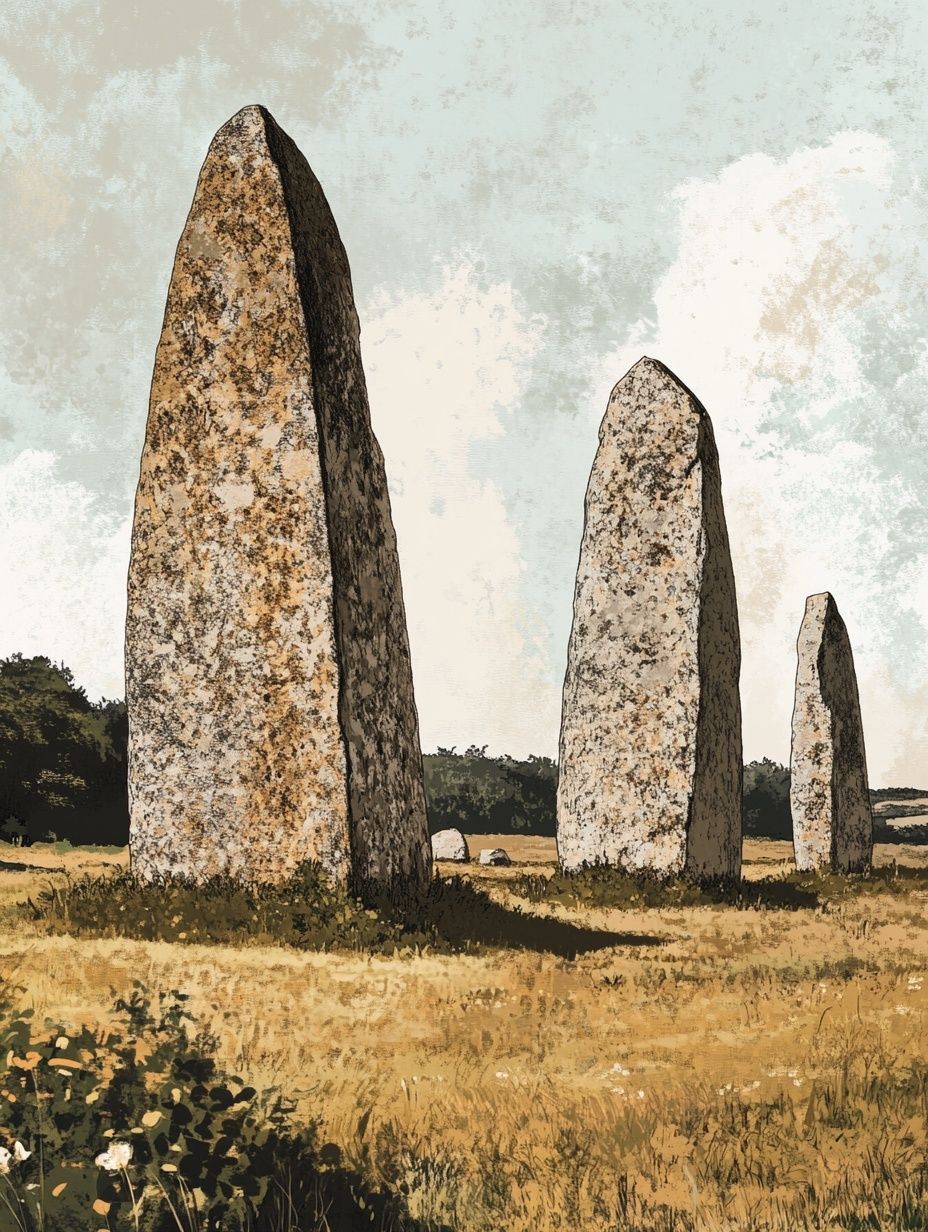

Brittany is a rugged peninsula on the northwest tip of France and "Breton" folklore has been heavily defined by its landscape: a place full of craggy coastlines, deep forests and thousands of prehistoric standing stones called menhirs (the word comes directly from the Welsh/Brythonic language: maen (stone) and hir (long)).

Read on to learn more about the history, folk stories and creatures of this beautiful part of France.

Published: 6th Dec 2025

Author: Sian H.

The origins of Breton folklore: Britain to Brittany

Before I get into the specifics, it's useful to understand why Brittany has different stories to the rest of France - why is this region still so heavily influenced by other cultures?

The great migration

Before the 5th century, the peninsula where Brittany now sits was called Armorica (a Roman name meaning "the land by the sea").

In Great Britain, the Roman Empire collapsed and the Anglo-Saxons (Germanic tribes) began invading.

To escape the violence, waves of Celtic Britons fled across the English Channel.

They settled in Armorica, displacing or mixing with the sparse local population. They renamed the land "Little Britain" or Breiz - which became Brittany.

The Breton language (Brezhoneg)

The immigrants brought their language with them. This is why the Breton language isn’t a dialect of French. It’s a Celtic language (specifically Brythonic).

- It’s a close relative of Welsh and Cornish (from Cornwall, England). A speaker of Old Breton could likely have understood a speaker of Old Welsh.

- For centuries, Breton was the main language of the region, especially in the west (Lower Brittany).

- This created a language barrier that acted like a shield. It stopped French culture and stories from taking over. Because the people couldn't read or speak French, they kept their own oral traditions, songs and legends alive in isolation.

How Breton folklore developed

Because the people came from Britain, they brought their British heroes with them.

This is why famous folklore figures like King Arthur and Merlin are a presence in Breton folklore - they’re part of the shared legends of the Welsh and the Bretons.

However, over time, the folklore naturally evolved:

- Adaptation: They took their existing gods and spirits and attached them to the new landscape. The pre-existing standing stones (menhirs) of Carnac were absorbed into their stories, often becoming "pagan soldiers" or "homes for dwarfs."

- Isolation: While the rest of Europe moved on to new literary trends, Brittany stayed isolated. The stories didn't change much for a thousand years, preserving very old Celtic beliefs that were lost elsewhere.

Today, Brittany is no longer cut off from the world and although the Breton language itself is fighting for survival (classified as severely endangered after losing the vast majority of its speakers), its unique cultural identity remains strong - kept alive by a people determined to remain distinct from the rest of France.

Breton folklore creatures & spirits

Fae (fairies) and sprites

In Breton folklore, like other Celtic fae, fairies aren’t just one type of being and they’re not sweet little creatures either (though they can still be helpful).

They’re often tied directly to the landscape and are generally viewed as the displaced pagan gods of the ancient world who have shrunk in stature but kept their powers.

The Korrigans

Stories of the Korrigans - like most fae stories - are mixed. The term is sometimes used as a catch-all for dwarf/sprite like figures but different tales describe them variously as dwarfish figures with wrinkled faces and red eyes and others as beautiful women who would transform into monstrous hags.

- They’re believed to live under the dolmens (ancient stone tombs) and also have strong ties to water (this coming from a link to the goddess Kerridwen/Cerridwen in Welsh mythology).

- They are the primary source of the "changeling" myth in Brittany - this same myth being prevalent in all Celtic lore. They’re obsessed with human vitality and will steal healthy human babies, leaving behind a wrinkled Korrigan child who eats constantly but never grows.

- Korrigans are intelligent and sometimes discussed engaging in complex interactions like forging metal.

The Korrigan as a predatory spirit

The Korrigan was often feared most as a kind of enchanting sorceress. One legend describes how she would trap travelers with powerful hallucinations, using her magic to disguise the dense forest as a luxurious castle.

Inside, she and nine handmaidens would seduce the victim, making him so obsessed that he completely forgot his real life, his wife or his girlfriend.

But at the first light of dawn, the spell broke. The Korrigan turned back into a repulsive hag and the castle dissolved into the reality of the woods: the carpets were actually moss, the silver cups were wild roses and the mirrors were nothing but stagnant puddles.

This particular type of story - the "conniving, deceptive woman" who tempts and leads "innocent men" astray, is one of the most common tropes in all of folklore and similar stories are prevalent all around the world. Like other tales, they obviously developed as a way to excuse and caution bad behaviour - read about other

monstrous and predatory folklore spirits here.

Gorics, Courils and Crions

These are regional names for the same family of dwarfish earth spirits who inhabit Brittany's ancient standing stones and ruins.

They share the same defining traits: they're small, immensely strong and obsessive. Locals believe they built the megaliths and now guard them.

Their primary threat is the dance; at night, they link hands around the stones and force any traveler they catch to join the circle, spinning them until they die of physical exhaustion.

A specific variation of Goric beneath the Castle of Morlaix also guards treasure, offering a single handful of gold to lucky mortals but punishing greed with violence.

The Nicole

It sounds innocent enough but the Nicole was a spirit that tormented the fishermen of the Bay of Saint-Brieuc and Saint-Malo.

As they were reeling in their nets, this mischievous spirit leapt around them and let the fish go, or he would loosen a boat's anchor so that it drifted on to a sand-bank.

The spirit is named after a real military officer who was infamous for being a tyrant. He commanded a unit of drafted fishermen and treated them with such brutal discipline that the locals hated him. His reputation for cruelty was so enduring that they honored him by naming this nasty spirit after him.

The Fées (The Great Fairies)

Although "Fée" is a direct translation for “Fae," (or fairy), in Brittany it also refers to a specific sub-species of Fae.

While the Korrigans represent the "common" earthy spirits, the Fées are the aristocracy - powerful, human-sized sorceresses who stand apart from the rest of the fae world.

The Margot:

This name is given to the rustic fairies of the moorlands, particularly in the Côtes-d'Armor (formerly the Côtes-du-Nord).

They appear as country women, are powerful but moody and are known to kidnap human midwives to assist with their own births, rewarding them generously if they are polite, but cursing them if they are rude. They are said to be able to make themselves invisible at will.

Similar stories are found across other Celtic lore though the figures themselves aren’t always as clearly defined.

Fées of the Houle:

"Houle" is the Breton word for a sea cave. These "Fairies of the Sea-Caves" live in the cliffs of the Haute-Bretagne coast.

They’re said to be invisible during the day because they cover themselves in "magic ointment". They’re beautiful, imperious figures and keep "sea cattle” - magical cows that graze on the clifftops during the day but must return to the waves at night.

In Scottish folklore, there is a slightly different version of these “fairy cows”, called Cro Sìth (or Crodh Sìth in the more modern spelling).

Spirits of death in Breton lore

Brittany has been described as the "Land of the Dead." In the local folklore, the barrier between the living and the deceased is incredibly thin. Unlike other cultures where the dead depart for a distant afterlife, in Brittany, the ghosts and spirits of the deceasd remain in the parish, living alongside their descendants.

Traditionally, the Bretons demonstrated respect for the dead as a community that required care and acknowledgement.

The Ankou

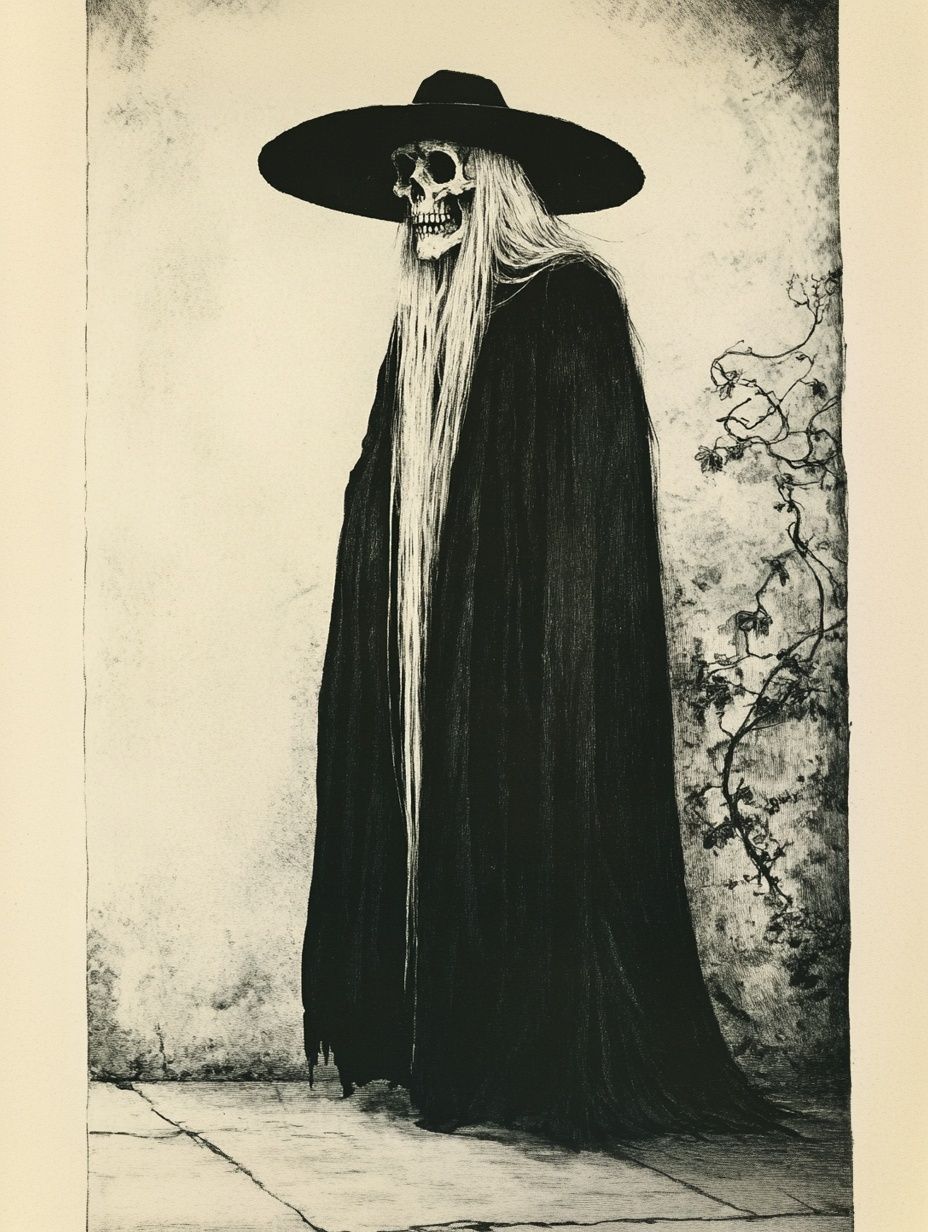

The Ankou is possibly the most significant figure in Breton mythology - he is the personification of Death, often referred to as the "Reaper of the Parish.”

This omen of death is often described as a tall, skeletal figure with long white hair, wearing a wide-brimmed felt hat and a long black cloak and tradition dictates that the last person to die in a parish during the calendar year becomes the Ankou for the following year.

In other versions, it is the first dead person of the year.

Similar to his Irish counterpart, the Dullahan, he travels in a cart (the Karrigell an Ankou) drawn by two horses - one lean, one fat.

The axle of the cart is silent except when it stops at a house to collect a soul, where it lets out a loud creak. This sound is a direct omen of death for the household.

The Anaon

The Anaon is the collective name for the "Souls of the Departed." In Breton belief, the souls of the dead wander the fields and lanes of the parish where they lived and are believed to suffer from intense cold and hunger.

On All Saints' Eve (Toussaint), families leave food (clotted milk or pancakes) and keep the fire burning so the Anaon can warm themselves.

They’re generally harmless if respected, but if the living neglect their duties - such as failing to leave food or performing the correct prayers - the Anaon will haunt the homestead, causing sickness or bad luck.

Enjoying this article?

Check out this authentic vintage source text of Breton folklore!

(Clicking the link will open the Mythfolks Etsy shop in a new tab.)

The Kannerez-Noz (Night Washers)

These are spectral washerwomen found at fords and lonely streams at midnight.

They’re a specific omen of death, similar to the Irish/Scottish Banshee, or more specifically the Scottish Bean Nighe.

They're seen washing the grave-clothes (or shrouds) of those who are about to die and if a traveler passes them, the washerwomen may ask for help wringing out the wet sheets.

If the traveler twists the sheet in the same direction as the washerwoman, they are safe. If they twist in the opposite direction, the washerwoman breaks their arms or drags them into the water to drown.

How lovely.

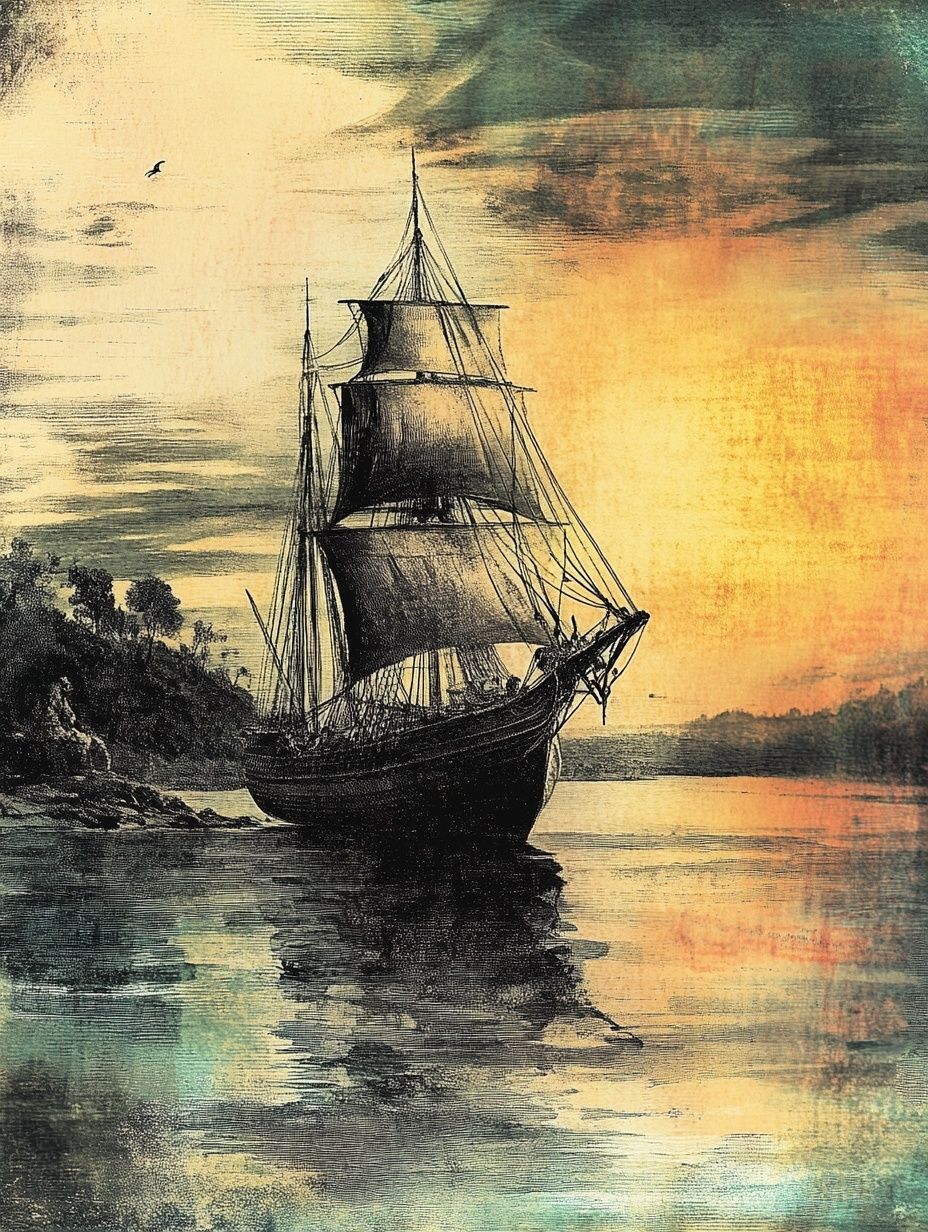

The Bag-Noz (the Night Boat)

Legends along the coast tell of the Bag-Noz, a phantom ship manned by the souls of the drowned and often seen sailing just before a sudden storm.

The crew are the souls of sailors who were lost at sea and never received a proper burial and their cries are said to be audible over the sound of the wind.

Werewolves (the Garwal)

Brittany has a dense tradition of lycanthropy. The Breton werewolf is known as the Garwal (similar to the French loup-garou which landed in Louisiana, French Canadian and other North American lore with dense French influence).

The Breton version of a werewolf is often a tragic figure or a victim of a curse, rather than a mindless infectious beast.

Bisclaveret

The most famous Breton werewolf story comes from the Lais of Marie de France. It tells of a baron who transforms into a wolf for three days a week.

He hides his clothes in a hollow stone to ensure his return to human form. When his wife discovers this, she steals his clothes, trapping him in wolf form until he is eventually hunted by the King and reveals his human intelligence.

In rural legends, men were often condemned to wander as wolves for a set period (often seven or nine years) as penance for sins.

Demons & Witchcraft

While Brittany is a land of saints, there is good detail about darker "Black Arts" that permeated the rural districts. The folklore acknowledges a potent underworld of sorcery, which isn't surprising given that

folklore around witches is especially significant in Celtic regions.

Witchcraft & the Grimoire

Belief in witches and dark magic remained strong in Brittany well into the early 20th century.

The details here are somewhat familiar having been used often in modern fantasy and horror storytelling but they do have a root in authentic folklore.

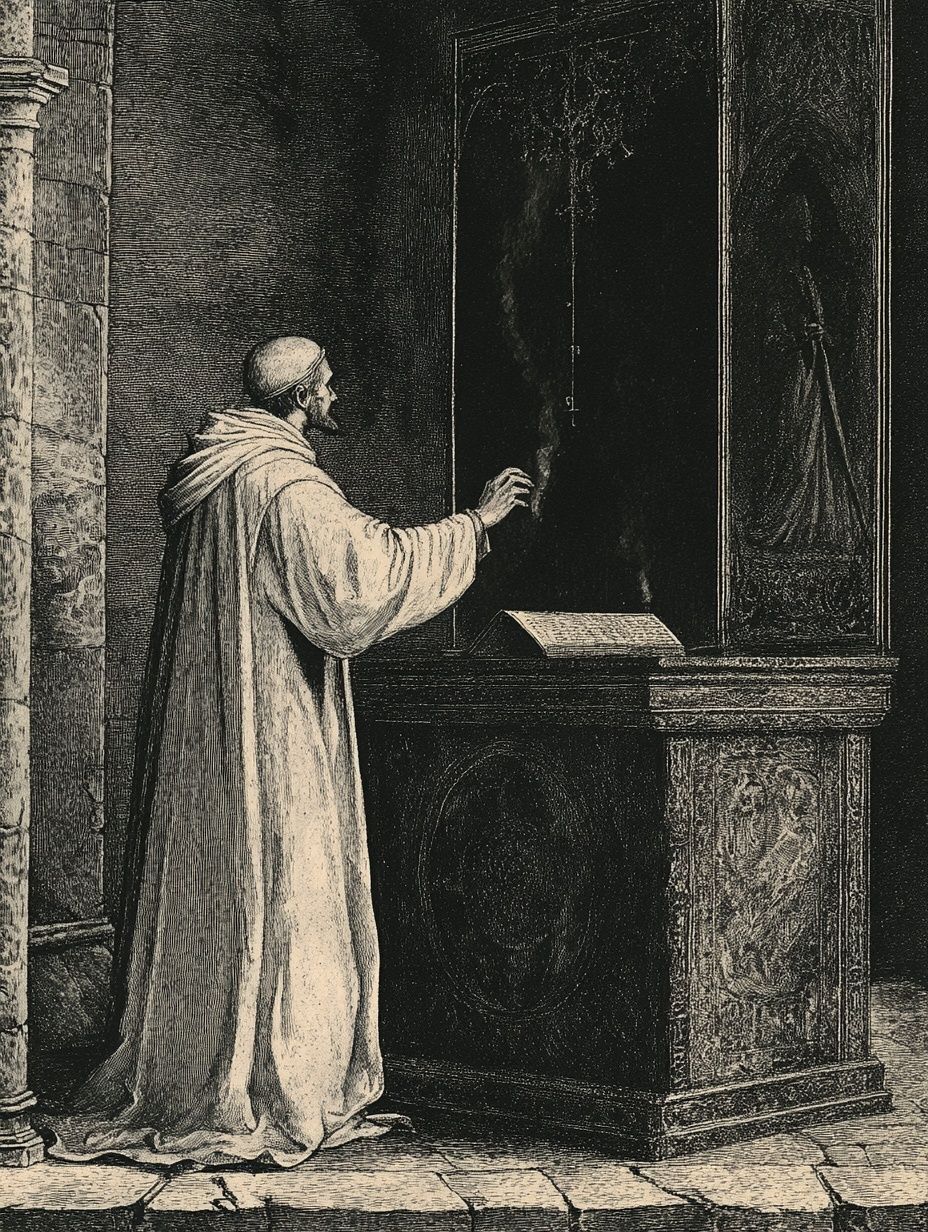

The source of a sorcerer’s power was often believed to be a "Black Book" or Grimoire, colloquially called an Agrippa (after the occultist Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa).

Legends suggest that these books were indestructible and that reading them required a pact with the Devil.

If you tried to burn an Agrippa, the book would often leap out of the fire unharmed, if you threw it in the ocean, it would swim back and be waiting dry on your table when you returned.

Only a priest could destroy it, usually by performing a specific ritual to exorcise the demon inside before burning it.

The Devil

The Devil figures prominently in Breton legends (as he does in all Celtic lore and other cultures too).

Many megalithic structures or complex bridges are attributed to the Devil. In stories, he offers to build them in a single night in exchange for the first soul to cross.

The locals usually cheat him by sending a cat or a dog across first.

In other legends, the Devil often appears as a handsome stranger in red, using vanity and lust to destroy the pious.

Saints as Sorcerers

The folklore describes saints possessing powers that mirror the pagan deities they replaced.

They could cure madness, blindness and rheumatism.

However, they were also capable of cursing those who disrespected them.

It was believed that a saint’s statue could inflict harm if the saint was angered, a concept that aligns more with animism than orthodox Christianity

Saints & miracles

Speaking of Saints…Brittany has a lot of old legends about these religious figures.

Saint Cornely (Cornelius)

Saint Cornely is the patron saint of horned cattle and a central figure in the folklore of Carnac, where his legend explains the origin of the famous standing stones.

As a Pope fleeing persecution in Rome, he escaped to Brittany but was cornered by pagan soldiers at the edge of the sea. With no means of escape, he turned to face his pursuers and transformed the entire Roman legion into stone, creating the rows of menhirs that remain frozen in their ranks today.

He is traditionally depicted surrounded by oxen, and farmers have long visited his shrine to bless their herds against disease.

Saint Pol (Paul Aurelian)

Saint Pol Aurelian, one of Brittany’s seven founder saints, is best known for a legend that twists the typical dragon-slayer story. When a dragon terrorized the Île de Batz, St. Pol didn't fight it with a sword.

Instead, he simply approached the beast and wrapped his long scarf around the creature's neck. Using the cloth like a leash, he led the tamed dragon to the edge of a cliff and ordered it to jump into the sea, getting rid of the monster without shedding a drop of blood.

The Pardons

The Pardon is a Catholic pilgrimage tradition that’s still practiced today, but the motivation for attending has changed.

Until the mid-20th century, the events were primarily functional: people attended specific Pardons to cure specific physical ailments, such as eye infections or snakebites.

While that medical aspect has faded, the distinct rituals remain active.

The "Troménie" at Locronan still involves a procession tracing a six-mile route through the woods and at Saint-Jean-du-Doigt, the festival is still marked by a mechanical angel descending from the church tower to ignite a massive bonfire.

Although Breton folklore definitely shares a lot with other Celtic traditions it can be partly separated by its intense physicality. It's a mythology carved directly into the granite landscape, where standing stones are petrified soldiers, sea caves house beautiful sorceresses and mysterious creatures live in the earth.

Check out more Celtic lore below.

Article sources

- Spence, Lewis. Legends & Romances of Brittany. London: George G. Harrap & Company, 1917.

Shop this vintage text about Celtic folklore from Brittany

I spend a lot of time digging through old and out-of-print folklore texts and curate selected titles as digital editions.

I used this comprehensive, early 20th century Brittany folklore book as a primary part of my research for this article and have re-packaged it in my Etsy shop for purchase.

Inside you'll be treated to a very broad range of Breton myths, legends, fables and more across topics like demonology and the supernatural, historical romance, religion and heroic tales.

A must-have resource for anyone digging into authentic Celtic folklore!

(Clicking the link will open the Mythfolks Etsy shop in a new tab.)

You might also like