Who were the old gods & goddesses of Babylonia and how were they related?

The first gods of Babylonia are well detailed in the creation epic, the Enuma Elish and I covered an overview on that topic here (also this vintage source text is a scholarly edition well worth digging into if you’re into the detail!).

But because it literally is epic, in this article I’ve done a separate round-up on all the deities as well as taken a look at how the ancient humans of Babylonia interacted with the gods in day-to-day life.

How these deities were related is

not straightforward so I’ve done my best to piece it all together…here goes!

Published: 26th Aug 2025

Author: Sian H.

The early gods of Babylonia

A short aside on syncretism - in simple terms, syncretism is a process where one civilization adopts the beliefs of another. The most familiar example is the way the Romans adopted the Greek gods and gave them new names. The Babylonians did the same thing, which is why their gods have deep roots in the Mesopotamian civilizations that came before them - the Sumerians and Akkadians.

So when we discuss the gods of Babylonia, we're often discussing deities who have a blended history and sometimes blurry origins. Gods that existed in Sumer often still existed in Babylonia but perhaps under a different name (but not always) or perhaps with reduced prominence. I've tried to explain these where relevant!

Anyway, let's go back to the beginning of Babylonian mythology - there were two primordial beings:

- Apsu, the god of fresh water,

- Tiamat, the goddess of saltwater

They weren’t gods in the way we think of them today but more forces of nature. Their union created:

- Lahmu and Lahamu: Often associated with the silt and mud that settled from the mingling waters. They represent the first solid matter in a world that was previously just water.

- Anshar and Kishar: These two followed and they symbolize the universe beginning to take shape and have boundaries. Anshar represents the "whole sky," and Kishar represents the "whole earth.”

These four also weren't fully-formed, human-like gods with personalities or powers. They were more like cosmic principles that emerged from chaos, paving the way for the more active and powerful gods who would later build the structured world.

Then came the beginning of the “human-like” gods, those that appear more like people with special powers rather than an abstract cosmic force as the previous lot were:

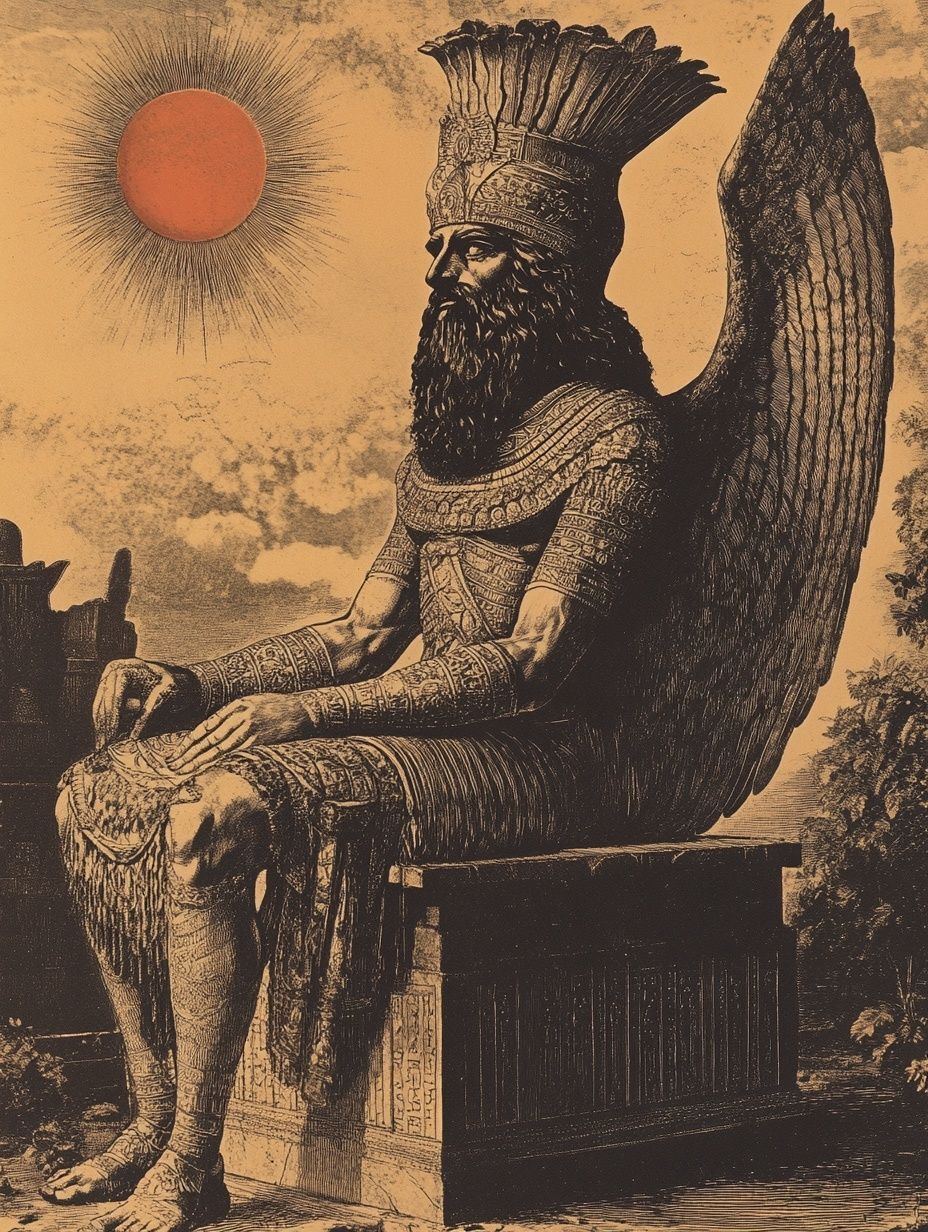

Anu - was the mighty sky god, son of Anshar & Kishar, and his son was:

Ea - the god of wisdom, magic and water, and then HE had a son:

Marduk - originally a minor god of agriculture, he went on to become the all powerful, all mighty king of the gods of Babylonia - which you can read more about here.

While Marduk ended up being the most powerful of all the gods, Anu and Ea were also considered very important.

The other gods of Babylonia

Still with me? Good.

After Marduk became king of the gods, the rest of the pantheon was structured into a divine government, with each deity assigned multiple roles and responsibilities.

Celestial gods

Sin, the moon god:

- His cycle was used to measure the months and time. Because the moon's cycle influenced the seasons, he was also associated with wisdom and fertility. His cult center (or his main home on Earth) was the city of Ur.

- Descended from: his parentage is usually considered to be Enlil, god of air, wind and storms, another (very powerful) Sumerian figure not dissimilar to the Greek Zeus and Ninlil, Sumerian goddess of the atmosphere. These two still existed in the Bablyonian pantheon but their roles were diminished once Marduk rose to power.

Shamash, the sun god:

- For the Babylonians, the sun’s light reached everywhere, making it a perfect symbol for a god who could see and know everything. He was therefore also the god of justice, truth and law.

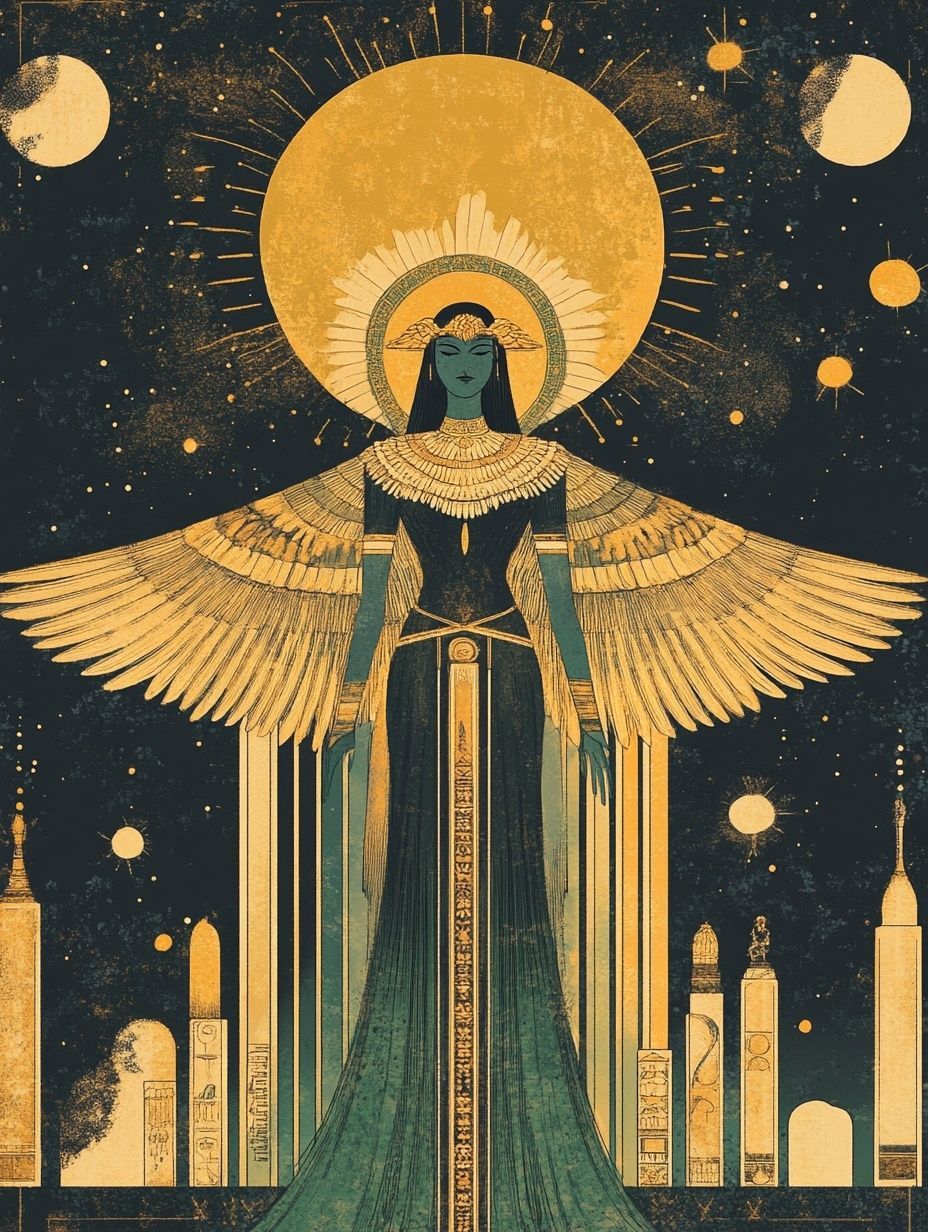

Ishtar, the goddess of love and war:

- She was the goddess of the planet Venus. She had two distinct sides to her nature: as the morning star, she was the goddess of love, beauty and fertility, but as the evening star, she was a fierce goddess of war and combat.

- Descended from:

Shamash and Ishtar were twins and the children of Sin and his wife Ningal.

The gods of the underworld

The Babylonian underworld was known as the "Land of No Return". It was almost like its own kingdom with a divine hierarchy. Authority over the countless souls of the dead was shared by two powerful deities who ruled as king and queen.

The Ruling Couple:

Ereshkigal, goddess of the underworld:

Ereshkigal is the original and eternal queen of the underworld. While earlier Sumerian myths tell of her being abducted and forced into the role, the Babylonians largely saw her as the realm's inherent ruler. Her authority was absolute and unchallenged until the arrival of her future husband.

Descended from: another child of Sin and sister to Shamash and Ishtar.

Nergal, god of the underworld:

Nergal was a god of the upper world, associated with plagues, pestilence, and the searing heat of the midday sun. In a Babylonian myth, he insulted Ereshkigal by proxy and was forced to travel to the underworld to apologize. Through a series of events involving seduction and threats, he became her lover and co-ruler. Their marriage established a joint, and often fearsome, rule over the dead.

Descended from: often considered to be another child of Enlil (Sumerian)

The Underworld Court

But a king and queen don't rule alone. The Babylonian underworld was managed by a court of minor gods who served the throne and handled the administration of death:

Namtar, the vizier:

As Ereshkigal's right-hand man and chief messenger, Namtar carried decrees from the underworld to the world above. He was also a god of fate and commanded dozens of diseases, acting as the divine agent of plague.

Belet-Seri, the scribe:

When a soul arrived in the "Land of No Return," it was the goddess Belet-Seri who recorded their name on a clay tablet. Kneeling before Ereshkigal, she served as the official record-keeper, making each soul's damnation permanent.

Neti, the gatekeeper:

The underworld was protected by seven gates, and Neti was their chief guardian. In the famous myth of Ishtar's Descent, it's Neti who confronts the goddess and, on Ereshkigal's orders, strips her of her power as she passes through each gate.

The Divine Judges:

The Anunnaki:

These powerful gods were the offspring of the sky god Anu. While many resided in the heavens, a specific group sat enthroned in the darkness as judges of the dead. This role is described in the Epic of Gilgamesh - Babylon's foundational epic poem about a hero-king's quest for immortality - where the judges pass sentence on new arrivals, adding a layer of grim, cosmic law to the afterlife.

Enjoying this article?

Check out this definitive vintage ebook on the Babylonian creation epic, Enuma Elish!

(Clicking the link will open the Mythfolks Etsy shop in a new tab.)

Gods of earth & war

Adad, God of Storms and Rain (Iškur in Sumer):

- Adad's role reflected the unpredictable nature of the Mesopotamian climate. He was a god of both destruction and creation, responsible for the life-giving rain that ensured a good harvest and the devastating floods and storms that could wipe out a city. His power over the heavens made him an unpredictable but essential part of daily life.

- Descended from: His father is often considered to be Anu, the sky god, but this varies in texts and the distinction between the lineage of the Babylonian Adad v.s the Sumerian Iškur isn’t always clear.

Ninurta, God of War and Agriculture

- Ninurta was a powerful warrior god who fought for the divine order and a god of agriculture. He was depicted as a great hero who defeated chaos monsters, most famously the Anzû bird, and established order in the world. He was also seen as a god who blessed the fields and ensured a good harvest, making him a central figure in both military campaigns and the daily life of farming.

- Descended from: another child of Enlil, husband of Gula

Here's a good example of the roles of gods crossing over - both Ninurta and Ishtar were responsible for war, but their specific roles differed:

- Ninurta was the god of organized, purposeful warfare waged to maintain divine order and protect civilization.

- Ishtar was the goddess of the chaotic, passionate and unpredictable nature of battle itself.

The gods of wisdom

Nabu, God of Writing and Wisdom:

- As the son of Marduk, Nabu was one of the most important gods in the pantheon. He was the god of writing, wisdom and scholarship. Writing was seen as a divine gift and Nabu was believed to hold the power of prophecy and knowledge. He was so important that, during the New Year's Akitu festival, his statue was carried from his temple to Marduk's, symbolizing his role as the keeper of divine knowledge and the son who could advise the king of the gods.

- Descended from: Marduk

Nisaba, Goddess of Grain and Writing:

- While she originated as an ancient Sumerian deity, Nisaba’s worship and mythology were adopted by the Babylonians. Her role represented the foundations of their society: agriculture and the art of writing. Her rule as goddess of writing was passed onto Nabu as the Pantheon evolved (because, nepotism much?).

- Descended from:

another child of Enlil or possibly Anu

Goddesses of nurturing and healing

The female figures who bore more famous children are often overlooked but are discussed as goddess figures in their own right - yet all their stories are defined largely by their husbands or sons so not quite in their own right.

Damkina, primordial mother goddess:

- She was the wise companion of the god Ea and the mother of Marduk, which established her as a divine mother at the very heart of creation. Her status wasn't minor; she was addressed in prayers as a "mighty queen of all the gods," and later goddesses inherited some of her titles, which demonstrates her foundational importance in the pantheon.

- Descended from: unclear, her primary role is discussed in relation to Ea and Marduk

Zer-panitum, Principal Goddess of Babylon:

- She's the consort of Marduk and her title, Beltis (or Bêlit), simply means "The Lady," signifying her supreme status.

- Like her mother-in-law, she wasn't just her husband's wife but a powerful deity with her own distinct character. She's directly linked with the creation of humankind, sharing that honor with Marduk.

- Descended from: like Damkina, her story is primarily defined by her husband (which directly contradicts my statement that she wasn't just her husbands' wife!).

Gula, Goddess of Healing and Medicine

- In the Babylonian pantheon, Gula was the go-to deity for anyone suffering from illness or injury. Her sacred animal was the dog, which was a common symbol of healing in ancient Mesopotamia and people would pray to her and leave offerings at her temples to petition for a cure. Her worship was so widespread that she had temples in many cities.

- Descended from: often identified as the wife of Ninurta

Lesser gods and supportive roles

Even though major gods like Anu ruled the heavens, the day-to-day work of the divine world was handled by a group of "lesser" or supportive gods. These weren't necessarily weaker, but they had very specific jobs that kept everything running smoothly.

Papsukkal, the Divine Messenger:

- Papsukkal acted as the trusted assistant and chief messenger for the great gods. His role was crucial for communication in a pantheon that was structured like a royal court. He was a loyal servant to supreme deities and a divine herald who delivered their decrees across the cosmos. Papsukkal also served as an intermediary, guarding the way to the higher gods and allowing people to pray to him for help.

A note on protective spirits vs. protective demons in Babylonia

There were other intermediaries that broadly fell into two camps - "protective spirit" and "protective demon". In Babylonian thought their roles were distinct and based on their inherent nature.

Protective Spirits (like the Lama):

- These were fundamentally benevolent beings, the Lama goddesses were guardian spirits who acted as divine intermediaries between humans and the higher gods. They were seen as part of the divine order, serving to help and guide humanity.

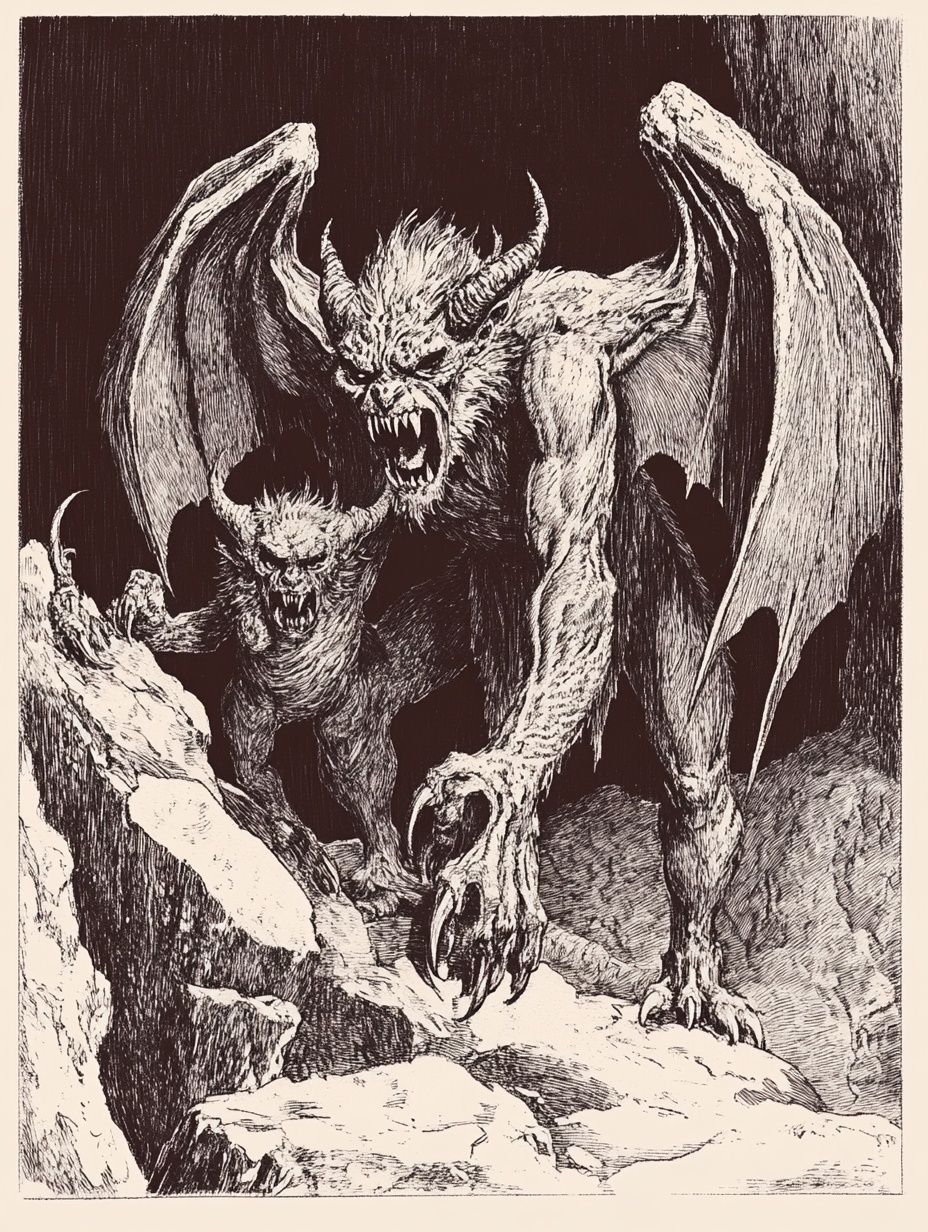

Protective Demons (like Pazuzu):

- These were inherently malevolent beings whose power could be instrumentalized for protection. Demons were often viewed as agents of chaos or punishers sent by the gods. They weren't worshipped, but placated or invoked out of fear and necessity. Using Pazuzu (King of Wind Demons and one scary being) for protection was akin to deploying a powerful weapon. It was a pragmatic and magical approach - fighting fire with fire - rather than an act of devotion.

The demons of Babylonian mythology, including those like

Alu, a sleep demon, need their own article - coming soon!

The relationship between humans and gods in Babylonia

For the average Babylonian, religion was an intimate and ever-present force, but one experienced far from the grand temples of the great gods.

The personal god:

- While major deities like Marduk or Ishtar were worshipped in grand city temples, they were considered distant and inaccessible to the common person.

- Instead, each family or individual had a "personal god" or goddess. These deities were viewed as "divine parents" who were intimately concerned with the well-being of their human charges.

- This relationship was maintained within the home, where families kept humble shrines and statues. People would offer daily prayers and small sacrifices to their personal god, seeking guidance, health and good fortune.

- This deity was seen as a personal advocate, an intercessor who would plead the individual's case before the great gods in the divine assembly.

Omens and aversion rituals:

- The gods were believed to communicate their will and future events through omens in the natural world.

- A Babylonian's daily life was filled with observing these signs - the flight of a bird, the shape of smoke, the behavior of animals.

- If an omen predicted misfortune, individuals weren't helpless. They could proactively engage with the gods through a ritual known as a nam-bur-bi (literally, "its undoing").

- This ritual was a direct appeal to the divine court, particularly to the sun god Shamash. By creating a representation of the ominous sign & destroying it, a person could symbolically take control of the threat and petition the gods to avert their fate.

Magic, amulets and incantations:

- The world was perceived as being full of supernatural forces, including numerous demons that could cause sickness and misfortune.

- Daily interaction with the divine, therefore, also involved magical practices. People wore protective amulets (like the head of Pazuzu) and recited incantations to ward off evil.

- Ritual specialists, or āšipu (exorcists), could be consulted to perform purification rites and banish demonic influences, invoking the power of the great gods to counter the forces of evil. This constant vigilance and ritual action were central to navigating the spiritual landscape of everyday Babylonian life.

New stories of ancient gods

Our understanding of Mesopotamian mythology is still a work in progress, with new stories still waiting to be translated from the ancient clay tablets.

Just this past June, a newly translated 4,400-year-old tablet tells a previously unknown myth about the Sumerian storm god Iškur (from which the later Babylonian Adad was born) being captured in the netherworld, an event that caused a period of drought and starvation.

Of all the gods, only a cunning fox volunteers to rescue him. The myth is weirdly fascinating since it suggests a helpless god in need of a hero, turning the typical narrative on its head. It also highlights the value placed on cleverness and wit in ancient society - brains over brawn and all that.

Like all mythologies, the structure and order of the pantheon of gods in Babylonia is deeply complex. Stories evolved from earlier stories, were recorded in ancient scripts on clay tablets and translated thousands of years later. And we're still translating new things everyday.

What is always clear to me is that humans have always had quite the knack for storytelling!

Don't forget to check out the creation story of Babylonia or get a more general overview of Mesopotamia in ancient mythology.

Article sources

- Langdon, Stephen. Sumerian Epic of Paradise, the Flood and the Fall of Man. Philadelphia: The University Museum, 1915.

- King, Leonard W. A History of Sumer and Akkad: An Account of the Early Races of Babylonia from Prehistoric Times to the Foundation of the Babylonian Monarchy. London: Chatto & Windus, 1910.

- Langdon, S. The Babylonian Epic of Creation: Restored from the Recently Recovered Tablets of Aššur. Oxford: At the Clarendon Press, 1923.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. Babylonian Life and History. 2nd ed. London: The Religious Tract Society, 1925.

- Sayce, Archibald Henry. The Religions of Ancient Egypt and Babylonia: The Gifford Lectures on the Ancient Egyptian and Babylonian Conception of the Divine. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1902.

Shop this rare, foundational ebook on the Babylonian creation epic, Enuma Elish

I spend a lot of time digging through old and out-of-print folklore texts and curate selected titles as digital editions.

The Babylonian Epic of Creation by renowned Assyriologist, Stephen Langdon, was one of the core texts I used to create my article series on ancient Babylon and Mesopotamia.

Langdon consulted the original cuneiform (clay) tablets in the British Museum to give a definitive and fascinating dive into the ancient beliefs discussed in this article - and much more (note: this is a scholarly text and not a light read!).

I've given the ebook a new cover, tidied and compressed the original scans and repackaged it into a convenient digital download at a great price. Check out this epic folklore text here.

(Clicking the link will open the Mythfolks Etsy shop in a new tab.)

You might also like