Types of witchcraft (and their folkloric roots)

In this article:

1. Archetypal witch types in myth and legend

b. The Healer

d. The Crone

2. Witch types by folk tradition and culture:

a. British & Northern European traditions

b. African witchcraft in folklore

d. Asian witch figures in folklore

3. Church-invented witch types

4. Modern witch inventions and revivals

5. Shared themes across cultures

6. What about Wicca, Stregheria and other modern witchcraft?

Witchcraft in folklore isn’t a single, uniform idea and "witchcraft types” haven't been chosen by witches themselves, but they've been assigned to them - through oral tradition, religious doctrine, local legend and centuries of repetition.

In this article I've broken down the types of witches as they appear in folklore - by role, culture and recurring themes.

You'll probably recognise some. Be bewildered by others. And by the end, hopefully have a good grasp of what types of witches have existed throughout history - and the ones still around today.

Settle in - it's a long one - but easily scannable if you're short on time!

Published: 9th Aug 2025

Author: Sian H.

Archetypal witch types in myth and legend

Before courts and church authorities created legal definitions of witchcraft, mythologies had already produced recognizable magical archetypes. They weren’t “witches” in the modern or historical legal sense, but their attributes - isolation, supernatural ability, liminality (or their existence in neither one space nor another) - became the foundation for later folklore.

The Sorceress

The sorceress is a powerful, lone figure who bends the world to her will using secret knowledge.

Unlike a priestess who serves the gods or a healer who serves the community, she works for her own ends and almost always disrupts social order.

She knows the rules in her own systems of magic and operates outside conventional morality.

Examples of the Sorceress in folklore:

- Greek mythology: This mythology - probably unsurprisingly - has many notable examples of the sorceress archetype (and other "witches"):

- Circe is a witch-goddess who lives alone on the island of Aeaea. In Homer's Odyssey, she famously transforms men into animals and must be outwitted through divine help. She represents the fear of uncontrolled female power and the unknown dangers that lurk outside a man's world.

- Medea is a princess descended from the sun god. In the story of Jason and the Argonauts, she uses her magical knowledge to help Jason, but her powers turn destructive when she is betrayed, leading her to murder her own children. Her tale shows how a magical figure who works for her own ends can become a force of tragic revenge.

- Phaedra is a noblewoman who uses magical knowledge and curses for her own destructive passions. In some versions of her story, she causes the death of her stepson after he rejects her advances.

- Morgan le Fay from Arthurian legend is a powerful sorceress and often an antagonist to King Arthur. Her magic is self-serving and she uses it to manipulate events and people, aligning her with the disruptive nature of the sorceress archetype.

- In

ancient Babylonia, certain women connected to the goddess

Ishtar wielded ritual magic to mediate between divine and mortal realms. These figures blurred the lines between priestess and sorceress, using their power for ceremonial purposes that often included sexual rites and death-linked ceremonies. They highlight that some sorceresses held a sanctioned, though liminal (i.e. existing on a threshold or in an in-between state), place within their society, rather than being entirely isolated.

The Healer

Embedded in the village or tribe rather than standing apart, this figure is called upon in childbirth, sickness, or misfortune. She may be known by name or title - cunning woman, wise man or bonesetter - and works with herbs, charms, spoken spells and ritual timing.

- The Herb-Wives of Anglo-Saxon England were healers who used herbs, charms, and spoken spells to treat illnesses. Their knowledge was practical and community-based, fitting the healer archetype perfectly. The Old English Nine Herbs Charm, a surviving manuscript, shows how they blended pagan and Christian traditions in their practices.

- In Celtic traditions, such healers often invoked saintly or fairy power to lend legitimacy to their work.

- In Slavic folklore, knowledge of plant medicine and anti-curse charms was passed matrilineally.

- Norse sagas reference lyfjaberg, a “mountain of healing,” associated with female herbalists.

- The Iatromantis in ancient Greece was a type of shamanic healer and seer. While the term is often applied to men, their role as healers who could also interpret divine signs shows an overlap with the seer archetype (see the next section). This highlights that these roles were not always strictly separate.

Folk healers were tolerated until their power threatened social cohesion. They might be recast as witches when a patient died, or as a strategy by emerging male-dominated medical and religious authorities to discredit rival practices and consolidate power. It wasn't their practices that changed, but public perception of them.

The Seer / Medium

Neither healer nor spellcaster, the seer communicates with hidden realms - the dead, gods or spirits of place - and interprets signs. They're often respected but remain outside everyday social structures, providing insight rather than comfort.

- Völvas in Old Norse culture were itinerant women who traveled with staffs and gave prophecies. They were often invited into chieftains’ halls to perform seiðr, a type of trance magic.

- In the Classical world, sibyls operated as oracles, often in a trance or under divine possession. While their words were seen as dangerous without priestly interpretation, not all prophetic figures held this position. For example, the highly respected Pythia at Delphi was a priestess whose pronouncements were central to Greek life and didn't require further interpretation.

- Cassandra, another example from Greek mythology (I did say there were quite a few!), is a powerful seer. She was a princess of Troy who was cursed by Apollo to speak true prophecies that no one would believe.

- In Siberian and Central Asian traditions, the Shamanka is another example. She enters a trance state to communicate with spirits, ancestors, and gods, much like a medium. Her role is to bring back knowledge and guidance from the spirit world to help her community, but she exists on the edge of that community.

- In

West African traditions, mediums communicate with ancestors or local deities (orishas, loa)

via possession, rhythm and ritual.

The Crone

This is probably the most fully folkloric of the types and one of the most recognisable - a constructed figure based on layers of storytelling, not real practice. She’s old, bent, often lives alone near the forest and usually causes trouble - not through cleverness or charm, but through curses, cannibalism or supernatural force.

- Hecate (Hekate) in Greek mythology was a goddess of witchcraft, crossroads and ghosts, often depicted as a crone or a triple goddess. She's a powerful deity, but her association with the dead, the night (Hecate was also strongly associated with the magic of the moon) and liminal spaces places her as the divine origin of many crone-like figures.

- The Cailleach from Irish and Scottish folklore is a primordial divine hag or crone. She’s a goddess of seasons, weather and the land itself, often appearing as a veiled, one-eyed old woman. She can be both a creator and a destroyer, embodying the ambiguous and powerful nature of the crone archetype.

- Baba Yaga, in Slavic stories, lives in a chicken-legged hut, flies in a mortar and pestle and alternates between helper and threat.

- The witch in Hansel and Gretel represents hunger, parental abandonment and fear of strangers all at once.

This archetype distills social fears: aging, childlessness, isolation - and knowledge that resists male control.

Witch types by folk tradition and culture

In most cultures, people made distinctions between different kinds of magic-users - not all of whom would have been called witches. Some cured disease; others caused it. Some spoke with spirits; others stole souls. Many of these figures were never named “witches” until outside observers imposed the label. Their roles were cultural, practical and sometimes sacred - until they weren’t.

British and Northern European Traditions

Cunning Folk

The

British cunning folk were community-based magical practitioners and healers - common in England, Scotland and Wales - who provided services like healing, divination, theft recovery and curse-lifting.

- Often Christian in identity, even carrying scripture as protective charm

- Used folk prayers, herbs, poppets, and written charms

- Distinct from “witches” in local understanding, though later authorities blurred the line

They appear in thousands of trial records - not as defendants, but as people accused witches had allegedly attacked.

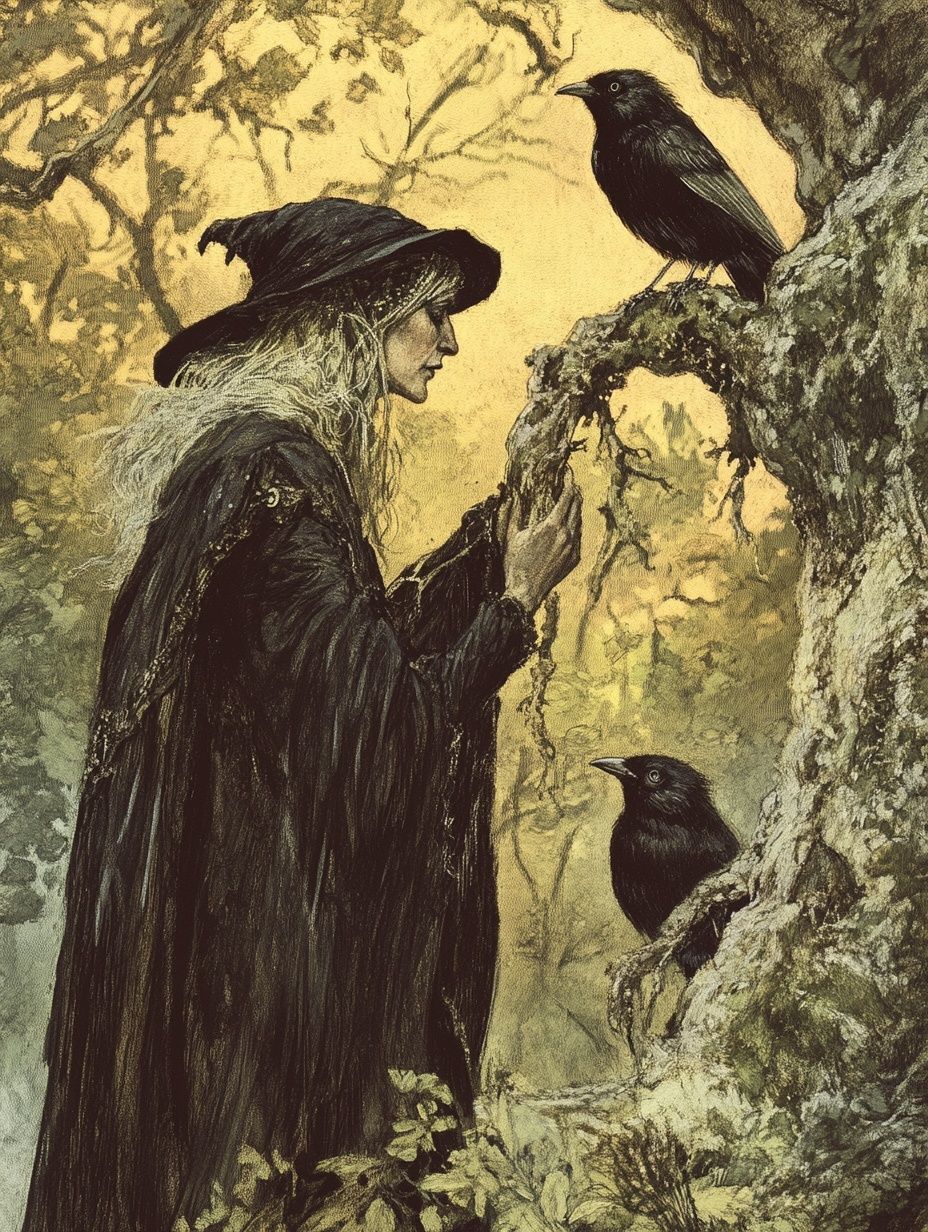

Hedge Witch

This term appears rarely in pre-modern sources but became popular in later folkloric writing. It refers to a solitary, rural practitioner whose knowledge is intuitive and rooted in the natural world.

- “Hedge” refers to the boundary between village and wilderness (a good example of a liminal space)

- Associated with herbal knowledge, animal omens, moon cycles

- Less a fixed role than a thematic cluster seen in multiple folk traditions

The hedge witch is closely related to the wise woman but with more emphasis on solitary practice and natural cycles.

Sabbath Witches

This is a type defined almost entirely by

accusation. These witches allegedly gathered at night to worship the Devil, desecrate Christian symbols and plot harm.

- Invented more by inquisitors than by actual belief systems

- Visualized in woodcuts: dancing around bonfires, kissing animal-headed demons

- In folk tales, elements like flying ointments, shape-shifting, and feast rituals survive as narrative fragments

While the Sabbath witch almost certainly never existed in practice, the imagery filtered into popular culture and lingered.

African Witchcraft in Folklore

Across African cultures, witchcraft is often understood not as a practice but as an invisible condition - a power one is born with or afflicted by.

The Harmful Witch

In Yoruba, Akan, Zulu and many other cultures, witches (often unnamed) are accused of causing illness, misfortune or death - not through ritual, but through spiritual means:

- Flying at night

- Leaving their bodies to attend secret meetings

- Eating the souls of the young or weak

- Possessing familiars like owls or snakes

These ideas don’t come from European influence but are long-standing, indigenous interpretations of misfortune and imbalance.

The Diviner or Healer

Often viewed as the opposite of the witch. Uses ancestral or spiritual power to diagnose illness, counteract curses or protect communities.

- May work with bones, shells, or natural signs

- Often undergoes initiation and carries spiritual authority

- In some traditions, they identify and “cleanse” witches through ritual or public confession

Folklore in these communities doesn’t deny the existence of witches - it reinforces their reality by assigning others the role of managing them.

American Folk Witchcraft

Colonial American folklore reflects a mix of Puritan suspicion, Indigenous worldview and African survivals.

Granny Witches

Found primarily in Appalachian and Ozark traditions. These were women (sometimes men) who learned herbal cures, midwifery, and protective charms through family lines.

- Used Bible verses alongside folk remedies

- Maintained root cellars, moon phase calendars, and plant lore

- Often seen as wise, but were vulnerable to accusation during periods of tension

These practices predate modern “witchcraft” revivals but are still carried on in rural traditions today.

Conjure Workers

In the American South, conjure (or rootwork) blends West African, Native and European folk systems.

- Practitioners used candles, powders, bottles, and graveyard dirt

- Services included love spells, protection, revenge, and healing

- Folk stories involve crossroads, spirit traps, and cursed objects

In these traditions, “witch” is often a label for someone dangerous - not someone who calls themselves that.

Asian Witch Figures in Folklore

While not always labeled witches, many figures in Asian folklore functioned similarly:

Japan:

- Onmyōji were court-appointed ritualists trained in yin-yang cosmology and spirit control

- Kitsune-tsukai (“fox users”) were feared individuals believed to command fox spirits, causing illness, obsession, or madness in others

- Accusations of fox sorcery often destroyed families, similar to witchcraft accusations elsewhere

China:

- Folk religion includes a long tradition of spirit mediums, usually female, entering trance to deliver messages from deities or ancestors

- Malevolent types included those who cast bone curses or used talismans for harm

- Many folk tales involve sorcerers controlling ghosts or demons, often punished in the afterlife

Church-invented witch types

Many of the most

recognizable “witch” figures - the ones burned, tortured and feared in the Early Modern Period - didn’t emerge from local belief. They were manufactured through

clerical imagination, systematized by inquisitors and spread through sermons, manuals and trials. These were top-down inventions - projected onto folk practices that often had no connection to the supernatural.

The Diabolical Witch

Created by medieval theologians, this figure doesn’t just work harmful magic - she does so in conscious alliance with the Devil.

- Believed to enter into a pact, formal or implicit

- Attends sabbats, renounces baptism, desecrates the Eucharist

- Gains powers from demons, not from nature or knowledge

This was an ideological tool: by framing witchcraft as heresy, the Church brought it under its legal and theological jurisdiction. The goal wasn’t to root out folk practice - it was to enforce doctrinal purity, especially as heretical movements spread.

The Sexual Deviant

Accusations of witches often involved charges of sexual perversion - intercourse with demons, seduction of priests or unnatural lust.

- This was less about evidence and more about anxiety: witches threatened gender order, male authority and clerical celibacy

- Female sexuality, especially post-menopausal (beyond reproductive control), was portrayed as inherently suspicious

- Night flights, animal transformations and “incubi” visitations often mirrored dreams or nightmares, but were interpreted as

proof of physical sin

These beliefs weren’t universal - they were pushed by a small group of clerics and inquisitors - but the invention stuck.

The Inverted Catholic

Much of what witchcraft was accused of doing was simply a reversed parody of Christian ritual:

- Holy water becomes poisonous

- Communion becomes cannibalism

- Processions become sabbats

- Priestly garments are worn by demons

This type of witch was pure projection that served to reinforce orthodoxy by defining its opposite - a total inversion of sacred order.

Modern witch inventions and revivals

Many "types of witches" circulating today - green witch, kitchen witch, chaos witch, sea witch - have little or no historical precedent. That doesn’t mean they’re inauthentic. But they’re part of a modern attempt to reclaim and organize something that was once imposed, erased or left unnamed. Modern witchcraft (often starting in the 20th century and reconfiguring in the 21st) isn't folklore, but it often pulls directly from it.

The Green Witch

A modern category grounded in nature work - herbs, plants, seasonal cycles. It overlaps with historical folk herbalists and hedge traditions, but uses updated terminology and often avoids religious framing.

No folklore tradition used this term, but the practices it points to - healing, gathering plants, living seasonally - are among the most widespread in pre-modern cultures.

The Kitchen Witch

An invention of the 1970s, but tied to deep roots in domestic spellcraft, protective charms and food-based magic.

- Historically, women were accused of harming others through food, milk and bread

- Objects hidden in the hearth or chimney were believed to protect the home

- Today, kitchen witches reclaim the space as sacred, not suspect

The Chaos Witch

One of the newer terms, often associated with post-Internet witchcraft. Usually denotes eclectic, result-oriented, often experimental practice.

- Draws from chaos magic (1970s–90s), a system rejecting dogma in favor of belief as a tool

- Historically, there’s no folkloric counterpart, but the attitude of improvisation has always existed among those excluded from formal systems

Sea, Storm, Bone, Tech or Other Thematic Witches

Social media platforms have accelerated a trend toward personal taxonomy: witches organize themselves not by lineage or geography, but by aesthetic, symbol or material of focus.

- “Bone witch” may indicate ancestral work or memento mori themes

- “Sea witch” may mean water-based ritual or emotional practice

- “Tech witch” merges digital tools with intention - not fantasy, but symbolic logic in modern systems

Again, these can't be cast as inauthentic, but they do tend to be more aesthetically driven rather than truly connected to deeper themes and coherent belief systems related to older or traditional witchcraft concepts.

Shared themes across cultures

Despite differences in practice, geography and belief, folklore around witchcraft tends to repeat the same few themes that reflect

shared human concerns.

Power in isolation

Witches in folklore almost always exist outside the village core: in the forest, in a hut, unmarried, widowed, childless or migratory. This physical and social isolation is often what marks them as suspicious.

- Those who operate outside kinship networks are harder to control

- Distance makes accusation easier - and defense harder

The witch becomes a symbol of the uncontrolled person - especially the uncontrolled woman.

Ambivalence, not evil

Most folkloric witches aren’t simply evil - they’re ambiguous.

- They heal and harm

- They help when asked and punish when crossed

- They offer services, but at a price

The "evil witch" is a relatively late invention. Earlier stories focus on balance, caution, and exchange - not morality.

Bodily knowledge

Many witches, especially women, are tied to the body: they know how it bleeds, how it births, how it dies...

- Midwives were often among the first accused

- Knowledge of fertility, abortion or healing threatened church authority

- The body became a battleground - and witches were accused of manipulating it, especially when outcomes failed

This wasn’t abstract knowledge. It was practical, hard-won and mostly transmitted outside written institutions.

Spiritual intermediaries

Whether feared or respected, witches are usually seen as operating between worlds:

- Between the living and the dead

- Between gods and humans

- Between nature and culture

This liminal role appears again and again - from African ngangas to Norse völvas, from Siberian shamans to Appalachian grannies.

What about Wicca, Stregheria, Brujería...?

You might be wondering where all the named types of witchcraft are - things like Wicca, Stregheria, Brujería, Pow-wow or Vodou.

You’ll often see them listed as “kinds of witchcraft,” especially in modern books or websites. But these aren’t types in the same way i've talked about so far.

They’re not just styles or categories - they’re traditions, belief systems or spiritual practices, many of which are modern or culturally specific.

They don’t fit neatly into a folklore timeline because they come from a different place and are often tied to identity, heritage, or spiritual belief rather than just old stories or fears.

A few examples:

- Wicca, probably the most well-known, started in the mid-1900s with a man named Gerald Gardner. It drew inspiration from folk traditions, ceremonial magic and ancient symbolism, but shaped them into a modern religion with its own structure, rituals and “types”. It’s not a type of witchcraft - it’s a full system that created new categories within itself.

- Stregheria, Brujería, Curanderismo and similar practices come from specific cultures - Italian, Latin American, Afro-Caribbean and others. They often mix local folklore with religion (usually Catholicism), healing traditions and older beliefs passed down in families or communities. These also aren’t just styles of witchcraft - they’re cultural traditions with their own histories, meanings and sometimes painful pasts linked to colonization or oppression.

- Systems like Pow-wow (from German-speaking communities in Pennsylvania) or Hoodoo (an African American folk practice) came out of real-world struggles. They were used for protection, healing and spiritual survival - not because someone chose a "path," but because it’s what people had.

I'll be digging into these separately, soon!

When we talk about witch types in folklore, we're really seeing a collection of different things: universal archetypes and characters from myth, real roles from history and fabricated figures invented to create fear.

The witch obviously isn't a single person. She's a constantly changing figure that people have used to make sense of the magical and the unknown. And understanding these distinctions can help us see each story as a source of inspiration for the creative worlds we build today.

Either way, the world of witchcraft remains an endlessly fascinating topic!

Don't forget to check out my

overview of the witch in folklore for a broader look at the historical aspects as well as mythology and you'll also enjoy my

dive into lunar magic & rituals.

Article sources

- Murray, Margaret. The Witch-Cult in Western Europe. Oxford University Press, 1921.

- Frazer, James George. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. The Macmillan Company, 1922.

- Ginzburg, Carlo. The Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Translated by John and Anne Tedeschi. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983.

- Thomas, Keith. Religion and the Decline of Magic: Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century England. Scribner, 1971.

- Wilby, Emma. Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits: Shamanistic Visionary Traditions in Early Modern British Witchcraft and Magic. Sussex Academic Press, 2005.

- Hansen, William. Ariadne's Thread: A Guide to International Tales Found in The Type of the Folktale. Indiana University Press, 2006.

- Evans-Pritchard, E. E. Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic among the Azande. Oxford University Press, 1937.

- Kieckhefer, Richard. European Witch Trials: Their Foundations in Popular and Learned Culture, 1300-1500. Routledge, 2014.

- Gardner, Gerald. Witchcraft Today. Rider, 1954.

Explore more witchcraft & magic folklore

These old folk healers were prevalent in the British Isles - learn more about how they came to be and the typical practices they performed.

Humans have been turning to blessed and sacred objects since the dawn of time. Get a full intro here.