The British cunning folk: healers, folk magic, rituals & remedies of old

In this article:

1. Who were the British cunning folk & what did they do?

2. The risks involved in practicing folk healing

a. 1736 Witchcraft Act and repercussions

3. Origins of a cunning person's power

5. Authentic ingredients & rituals of the cunning folk

6. Did the cunning folk genuinely believe in their magical powers?

This article contains great authentic details for writers and storytellers who want to create original witch or healer characters or ritual details.

It’s not new news that since time began, humans have faced daily threats of illness, injury and misfortune.

In Britain, for centuries, the Catholic Church used to offer saints, shrines and holy water to cure sickness or protect against bad luck.

But in the 16th century, the Reformation transformed the religious landscape, shifting Britain to Protestantism and removing these authorized rituals.

The common population couldn't afford doctors and so the cunning folk, or local folk healers, emerged to fill the gap.

Let’s take a look at who these people were in post-Medieval Britain, what they claimed to be able to do and the things they used to “heal” (I’ve got a few disgusting details for you, fair warning!).

Published: 21st Dec 2025

Author: Sian H.

Who were the British cunning folk and what did they do?

In the time period we’re talking about - roughly 1500-1900 - beliefs in dark witchcraft (maleficium) provided a rational explanation for inexplicable misfortune and illness in day-to-day life.

Doctors were often responsible for designating an illness or death they couldn't explain to witchcraft and generally, witches were seen by most people in a binary fashion, as either good (white) or bad (black).

Folk healers like the cunning folk, or cunning person, were usually considered "good" and their primary trade was diagnosing and countering this “bad” witchcraft.

And although healing illness was a primary goal, they also offered a broad menu of divination and other “magical” services, including finding lost property, identifying thieves and arranging love matches.

While similar practices operated across the British Isles and Europe and 'cunning folk' is now often used as a catch-all term, the label specifically originated in England and Wales and it was here that the profession flourished most openly. Alternate names for a cunning person included “wise man/woman” (especially in northern England) and in Wales, "Dyn Hysbys” (the knowing man).

A core tool in their professional kit was the use of charms - objects and/or words believed to create magical power. While a neighbor might know a simple prayer for a burn, the cunning folk had extensive collections of written and spoken charms for a wide variety of ailments that they used in their day-to-day operations.

And they didn’t act out of pure kindness - they charged a fee for their services accepting coins, gifts or future favors in return.

Cunning men or women?

Both men and women practiced the folk healer craft and although it’s not definitive, historical evidence suggests the majority were men - roughly two-thirds, according to some historians . This is the opposite to “evil” witches where around 75% were purported to be female.

This split was most likely due to social factors. Access to education for healers was key; advanced practices often required the literacy to read almanacs or spellbooks and men were far more likely to be literate.

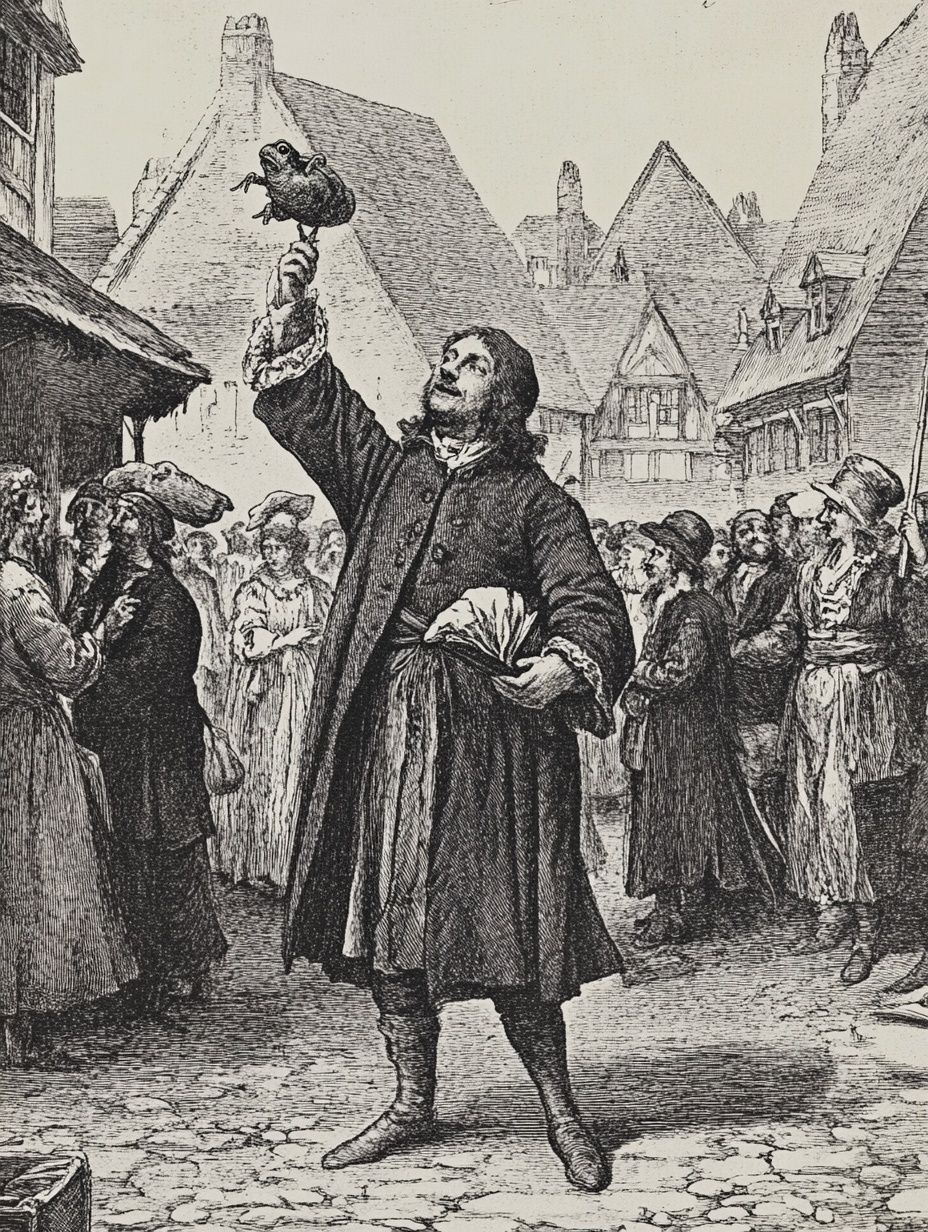

The Toad Doctor - a specific type of folk healer

The healer marketplace also supported niche specialists and charmers who focused on a single disease. A Toad Doctor was a specific type of itinerant healer who treated Scrofula (or "The King's Evil"), a glandular tuberculosis.

While the cunning folk handled everything from curing warts to finding stolen spoons, the Toad Doctor dealt exclusively with this medical condition.

They were famous for carrying bags of live or dried toads, believing the animal possessed a sympathetic connection to the disease that could draw the sickness out of the patient.

The physical alternative to the cunning person - the bone-setter

Although this article is about the “magical and spiritual” side of folk healing in post-Medieval Britain, it’s useful to also understand the physical side of old folk medicine.

Bone-setters - and it’s all in the name (!) - specialized in the manual treatment of fractures, dislocations and sprains. They were often blacksmiths or farmers by trade and they used their physical strength and hereditary techniques to reset injured limbs.

They were essentially the practical counterpart to the cunning folk, providing mechanical solutions for physical trauma for people who couldn’t afford licensed medical care (though in the times we're talking about, the licensed care wasn’t, in reality, much more advanced).

The practice of being a folk healer - or risky business

It’s not surprising that operating in any kind of “witch” or “magic” capacity at this time was incredibly risky - most of us have at least a top level awareness of the witch persecutions and trials in western history.

A folk healer’s clients were often desperate and their desperation made them willing to pay, but it also made them dangerous.

A failed cure could quickly lead to accusations of fraud or, worse, that the Healer's magic was the true cause of the problem.

I mentioned earlier that the cunning folk were generally seen as performing "good" magic, but it didn't always stop suspicion when things went wrong. There are a number of records of local healers being swept along in the witch frenzy and being tried and executed as witches during this time.

To avoid unwanted attention, many cunning folk maintained a respectable public trade. Running an alehouse or a smithy (blacksmith) was ideal, as it placed them at the centre of village gossip.

The most common cover, however, was that of a high-street herbalist, which allowed them to deal with the public and sell their magical services discreetly.

The 1736 Witchcraft Act and the repercussions for folk healers

In 1736, the Witchcraft Act twisted things round from a legal perspective.

Before, a folk healer’s fear was being accused of evil witchcraft and sentenced to death.

Now they risked being punished for the pretence of being a witch. The law essentially made it illegal to say or demonstrate that you had magical powers of any kind (though Capital Punishment was also removed so they now faced long jail sentences instead of being hanged - burning witches was more prevalent in continental Europe but rare in Britain).

In legal terms, witches were no longer evil, but fraudulent, a bunch of charlatans.

Of course, although the law had made this distinction, it would be a long time before those widespread beliefs followed and magical practices continued all throughout the 18th and most of the 19th centuries with aplomb, gradually declining to near non-existent by the early 20th century.

(Of course since then and

still today, various beliefs in witches and magic exist, but I mean at a total national level, community beliefs had well diminished by this time).

Origins of power or how a cunning person “received their magic”

A cunning person's power had to have a source to be believed. It wasn't enough to simply declare oneself a magic-user; the ability had to be legitimized through a story of origin. These were some of the main ones:

The seventh son:

It was a popular belief that a seventh-born son possessed natural healing abilities. Most often this meant the seventh son born in a row, but the most powerful claim was to be the seventh son of a seventh son.

This power was also believed to exist in female lines, with a seventh daughter of a seventh daughter being considered equally gifted.

This particular belief of the “7th” born was noted in multiple countries/regions including France, where the seventh son was known as a “Marcou”.

Gifted by supernatural creatures:

The most commonly claimed source of supernatural power origin was an encounter with fairies (fae). In Cornish (Celtic) folklore, a 17th-century servant, Anne Jefferies, claimed that after meeting "six persons, of a small stature, all clothed in green," she developed the ability to heal by touch and was fed by the fairies themselves.

Learned through apprenticeship & observation:

Magic was a trade and it could be learned like one - not in a formal academy, but through practical, informal means. Much of the knowledge was passed on verbally from a relative or a neighbour, as part of an informal exchange of knowledge within the community.

Aspiring practitioners would also learn by carefully watching established cunning folk and picking up their ideas and techniques.

Principles of the cunning folk “magic”

Beyond the practitioner's personal origin story, the folk healer craft was grounded in core magical beliefs that the community understood and these same principles can be found in other folk healer practices from global folklore. This was the theory behind their practice:

Sympathetic magic:

This was the foundational principle, based on the belief that "like affects like." Magic worked by creating and manipulating a mystical connection between an object (like a doll or a lock of hair) and a person.

Transference:

This was the key action of sympathetic magic. Sickness and curses weren’t destroyed but were believed to be tangible things that could be physically relocated. A folk healer's job was to draw the affliction out of a person and move it into an object, an animal or a running stream.

Authentic rituals & ingredients of the cunning folk

Now we get into the gritty magic details! The cunning folk carried or sourced tangible objects to use in their rituals - as referenced upfront, there are a couple of unpleasant details in this section.

Counter-Magic:

When fighting a curse, tools were aggressive and personal.

Witch bottles: This was a primary weapon against dark magic and there were different ways they might be used.

One example was filling a bottle with the victim's urine, nail clippings or hair, along with sharp objects like pins, bent nails and thorns. It was then corked and either buried or heated in a fire. The bottle represented the witch's bladder and the ritual was meant to cause them excruciating pain, forcing them to break the spell.

Scratching: A more direct approach. It was widely believed that drawing a witch's blood would break their power. The most potent method was called "drawing blood above the breath" (scratching the forehead), but a frantic victim would often just try to scratch their tormentor's hands or arms to get the job done.

Divination:

To find a person - whether it was a thief or a future spouse - the methods were ritualised pieces of theater.

Bible and key: A door key was placed inside a Bible at a specific verse. The book was bound shut and suspended by the key's ring. As the names of suspects were recited, a sudden turn or fall of the Bible was taken as proof of guilt.

Sieve and shears: A similar method where a pair of shears was stuck into the rim of a sieve, held aloft by two people's fingertips. As suspects' names were read aloud, the sieve would mysteriously turn or fall at the name of the thief.

Written charms & amulets

Cunning folk often provided written charms as physical protection.

The Abracadabra charm: Today, "abracadabra" is a cheesy phrase for stage magicians, but historically it was considered a word of real power.

It was most often written in a decreasing triangle shape on a piece of paper and worn as a potent amulet. Its specific purpose was to cure ague, a historical term for a recurring fever that involved fits of intense shivering and sweating, similar to malaria.

Holed stones: A stone with a natural hole through it. Not for general luck, but a specific tool used to see things that were otherwise invisible, such as fairies or spirits.

Grim cures

Some historical “cures” were deeply unpleasant:

For thrush (in a child): One directive was to hold a live frog's head in the child's mouth until the frog died.

For toothache: An example of transference, one ritual included making the patient's gum bleed with a new nail and then driving that nail into an oak tree. The pain was believed to be transferred into the tree.

Other magical components

Other ingredients a cunning person might keep in their possession.

Dragon's blood: Sounds like something made up from a mythical beast, but this is a real, reddish-brown tree resin harvested from several tropical trees of the Middle East.

As a valuable commodity used in everything from varnish to medicine, it was a regular import into British ports during this period.

A folk healer would have purchased it from a local apothecary or chemist who stocked such exotic goods and its primary use in folk magic was as a potent ingredient in love charms.

The Black Book: A famous “magical” object - this was the cunning person's most valuable tool and a practical, handwritten ledger of charms, herbal recipes and astrological charts. It was a professional manual and, if found by authorities, damning evidence.

Dangerous herbs: Some practitioners used their herbal knowledge maliciously, employing cocktails of poisonous plants like belladonna, hemlock and bryony to induce or prolong symptoms in a client, either to "prove" a diagnosis of witchcraft or to extract more money for a cure.

Did the cunning folk really believe in their magical powers or was it all a performance?

While the law had decided that folk magic practioners were all charlatans, it’s impossible to know for sure whether the cunning folk genuinely believed in their “powers” or not.

Several historical sources offer clear examples of deliberate fraud and deception but proving genuine belief is more difficult, as practitioners rarely kept diaries detailing their faith in their own magic.

However, historians generally conclude that in all probability, while some were actively deceptive, at least some practitioners completely believed in their power.

The most interesting aspect is the middle ground. Sources suggest that even when practitioners used tricks, it didn't necessarily mean they disbelieved in magic entirely.

A cunning person might genuinely believe in their craft but still use a bit of sleight-of-hand to help convince a skeptical client or guarantee a result, seeing the deception as a tool in service of the overall magical outcome.

Magic and healing have existed as long as humanity itself. While folklore and history often focus on grand mythology, the true story of folk practice is far more grounded and in post-medieval Britain (and indeed most other parts of the world), this tradition manifested as a necessary, day-to-day trade.

The cunning folk in their "witch-like" roles operated as ordinary professionals earning a wage. They took the ancient concepts of protection and cure and applied them to the immediate needs of their communities. Their legacy is ultimately one of practicality - a transaction between practitioners trying to make a living and ordinary people trying to live.

Explore more about the

different types of witches and other magic practitioners and rituals in folklore below.

Article sources

- Kittredge, George Lyman. Witchcraft in Old and New England. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1929.

- Black, William George. Folk-Medicine: A Chapter in the History of Culture. London: Elliot Stock, 1883.

- Davies, Owen. Witchcraft, Magic and Culture 1736–1951. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999

Explore more witchcraft & magic folklore

Take a trip through the history of witchcraft from ancient stories to the witch hunts of the Middle Ages.

There are many different classifications for witches and many of them have ancient roots. Learn all about them here.