The real Fae of Europe: separating folklore from fantasy

The term "Fae" or "Faerie" is often associated with modern fantasy depictions of small, winged, pretty beings.

But, in Celtic and Gemanic folklore, the real Fae - the authentic "Fae" - are a powerful, non-human race from a parallel "Otherworld," bound by alien rules and sometimes dangerous.

These beings were a significant part of daily life, representing forces of nature, the spirits of the dead and explanations for phenomena that were otherwise incomprehensible.

In folklore, they are one of the most complex, broad classifications of supernatural creatures and there is no one definitive way to view them - there are seemingly endless variations and local adaptations.

But we can still unpack all these stories to learn about them. So what types of Fae are there? Where did they come from and what should you do if you meet one (according to our ancestors)?

Read on to find out.

Updated: 7th Dec 2025

Author: Sian H.

Defining the "Fae" as a folkloric category

The modern English word "Fae" derives from the Old French fae, which in turn was said to derive from the Latin "Fāta". There are also many other variations that mean the same thing - fay, fēe, fey and so on.

The related term "Faerie" comes from the Old French faierie.

In folklore, these terms are now used to describe a broad category of supernatural beings that share a set of core characteristics:

- Otherworld connection: The Fae are believed to live in a parallel realm, often referred to as the Otherworld or Faerie. This realm isn't on a different planet as such, but co-exists with the human world, accessible through liminal - or transitional - places like ancient burial mounds, caves, stone circles and bodies of water.

- Amoral nature: Folkloric Fae don't operate on a human-centric moral axis of "good" and "evil." Their behaviour is better understood as amoral, governed by a strict and alien code of conduct. They can be helpful or hostile depending on circumstances and whether they've been shown the proper respect. An act of kindness might be rewarded, but a perceived slight could lead to ruinous retribution!

- Link to nature and place: Fae beings are often intrinsically tied to the natural landscape. They're often spirits of a specific river, forest, or mountain. This belief reflects a pre-industrial worldview where the natural world was seen as an active and often sentient force that had to be appeased.

It should be noted that the term "fae" and its synonyms, as discussed in this article, are

specifically related to Celtic and Germanic lore - similar beings from other parts of the world may resemble them, but are not actually classified as fae.

Anthropological origins of Fae belief

Academic folklore study suggests that belief in the Fae arose from several distinct, often overlapping, sources that provided explanations for the world.

- Euhemerism (Diminished Deities): Euhemerism is the theory that myths are derived from historical events and figures. In this context, it suggests that Fae are the diminished forms of older pagan gods. A primary example is the Tuatha Dé Danann from Irish mythology, a group described in medieval texts like the Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of the Taking of Ireland) as a supernatural race with divine attributes. According to the mythology, after being defeated by the mortal Milesians, they retreated into the hollow hills and burial mounds (sídhe). Over time, they became known in folklore as the Aos Sí (pronounced Ais Shee, meaning "the people of the mounds"), the aristocratic Fae of Ireland.

- Personification of Natural Forces: Many Fae represent the dangers and dynamics of the natural world. The Germanic Nix (or Neck) were malevolent water spirits who personified the very real risk of drowning in rivers and pools. Belief in these beings encouraged caution and respect for dangerous natural features.

- Social and Psychological Functions: Fae-related beliefs often served as a framework for understanding and coping with societal issues. The changeling myth, prevalent across Europe, involves a belief that the Fae would steal a human infant and leave a sickly Fae substitute in its place. Anthropologists and historians theorize that this belief served as a social coping mechanism to explain undiagnosed congenital disorders, developmental disabilities, or sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) in a pre-medical society. It provided a supernatural reason for a child's failure to thrive.

A classification of Fae-like beings by type and region

The Fae aren't a monolithic group and they can be broadly classified by their typical domain or function, with related concepts appearing in different cultures.

The Nature Spirit (Genius Loci):

These are beings intrinsically bound to a specific location (genius loci is Latin for "spirit of the place").

- Scottish: The Ghillie Dhu is a solitary fae guardian of the birch woods. Clothed in leaves and moss, his lore is directly tied to his specific forest, which he protects from intruders.

- English/Scottish: The Urisk is a wilder spirit, more commonly found near lonely pools and waterfalls. While sometimes described as a "wilder" Brownie, his primary domain is the natural, untamed place, not the home.

- Welsh: The

Gwragedd Annwn

are beautiful spirits from the Fae Otherworld (Annwn) who emerge from Welsh lakes to

marry mortal men. They bring magical cattle and great prosperity, but this pact is bound by a strict, literal taboo, such as "never be struck by iron." The tragedy is that this rule is always broken accidentally - a careless tap with a bridle or glove is all it takes to void the contract instantly, forcing her and her magic to return to the lake forever.

The Domestic Spirit:

These beings attach themselves to a human household and can be either beneficial or troublesome.

- English/Scottish: The Brownie is the classic domestic spirit of this region. It's a solitary, helpful being that performs chores at night in exchange for a bowl of milk or cream. They are famously averse to being given clothes, which they see as an insult and will abandon a house if treated disrespectfully.

- English: The Boggart is the darker counterpart to the Brownie It is a mischievous, tormenting

household spirit that causes poltergeist-like activity. In many stories, a Boggart is what a Brownie becomes after it has been offended by the family.

The Death-bringer:

These Fae are specifically associated with death, disaster or misfortune and the Gaelic traditions of Ireland and Scotland feature some of the most famous examples.

From Irish Folklore:

- The Banshee (bean sídhe, meaning "woman of the mound") is perhaps the most well-known. She's an ancestral spirit whose sorrowful wail, or keening, foretells a death within one of the old Gaelic families (like the O'Neills or O'Gradys). Her omen is auditory; she is heard, not seen.

- The Dullahan ("dark man") is a headless Fae who rides a black horse and carries his own glowing head (with many other physical variations depending on the source). The Dullahan is an active participant in death, riding to a victim's home and calling their name to summon their soul.

From Scottish Folklore:

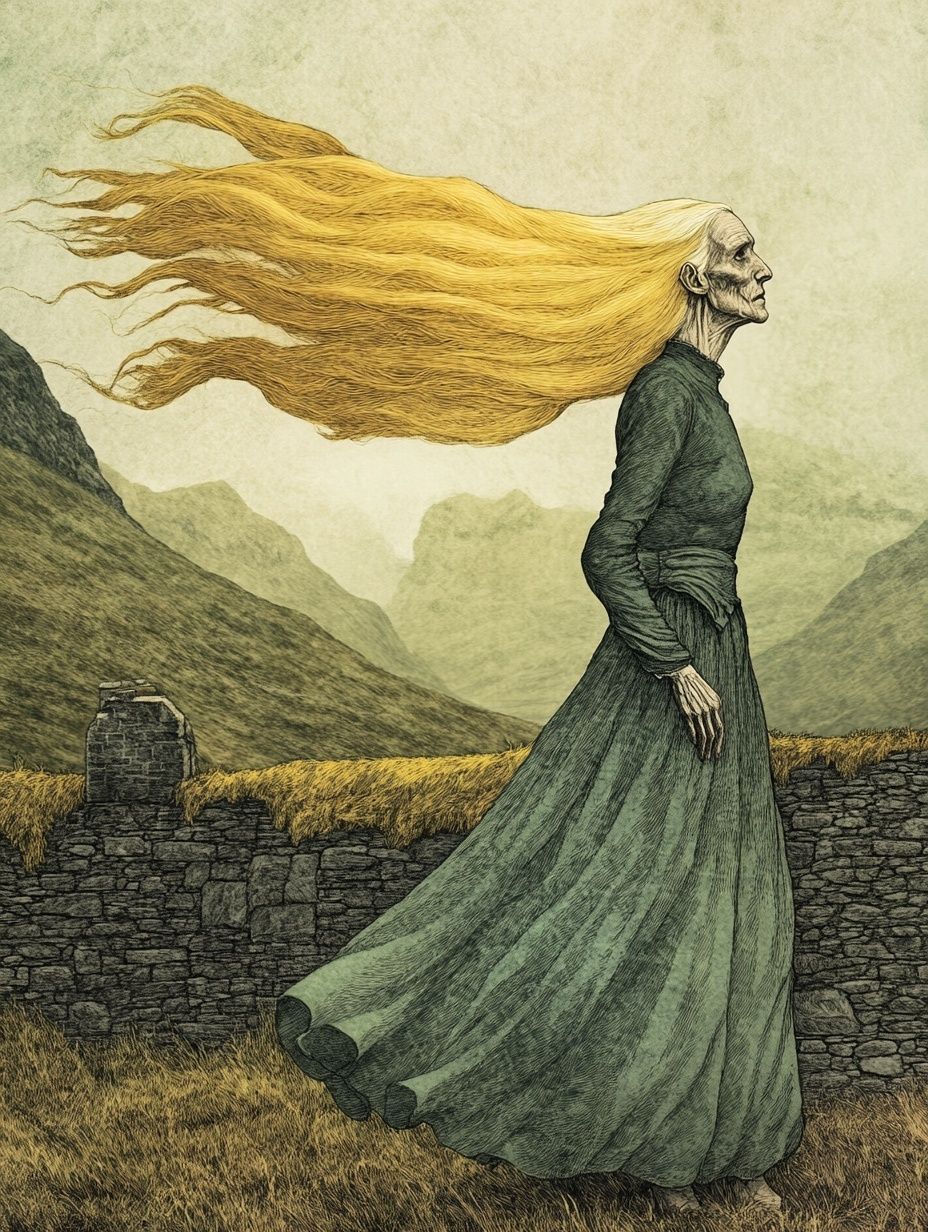

- While Scotland also has tales of banshees, a distinct and famous harbinger is the Bean Nighe ("washing woman"). As a specific type of banshee, she is a death omen seen at lonely streams, washing the bloody clothes of a warrior who is about to fall in battle.

Also see

the Ankou in Breton folklore.

The rules of interaction: taboos and protections in Fae lore

Folklore is full of practical advice for surviving an encounter with the Fae and these rules reveal a great deal about the perceived nature of these beings.

- Prohibition on Fae Food: A mortal who consumes food or drink from the Otherworld is permanently bound to it and cannot return to the human world. The Fae feast is a magical trap; eating the food is the same as signing an unbreakable contract. This is a central plot point in the ballad of Tam Lin, who was captured by the Fairy Queen; he can still be rescued by his mortal lover specifically because, while living among them, he "ne'er let [their] meat nor drink come in."

- The Power of Names: It was considered extremely dangerous to tell a Fae your full name, as this would give the entity power over you. Conversely, knowing a Fae's true name could grant a mortal some measure of control. As a result, euphemisms like "The Good Folk," "The Gentry," or "The Fair Folk" were used to refer to them indirectly and avoid attracting their attention.

- "Cold Iron": Iron was the most common and potent ward against the Fae. The two main theories for this are:

- 1) As a product of human technology and civilization, refined iron is anathema to the wild, pre-industrial magic of the Fae.

- 2) The process of smelting iron was historically seen as a powerful act of transformation, imbuing the metal itself with protective, anti-magical qualities.

- Other Aversions: Other common protections included running water, which Fae were often unable to cross, as it was seen as a pure and moving boundary between worlds; salt, a symbol of purity and preservation; and wood from the rowan tree, which has a long history in European folk magic as a protective charm.

The Fae economy: pacts, tithes and liminality

Beyond simple rules of etiquette, Fae folklore is governed by a complex system of debts, bargains and tributes that function like a sort of supernatural economy. Understanding this system is key to understanding their motivations.

- The power of a bargain: A deal with the Fae is magically binding and absolute. They can't break their word, but they are masters of loopholes and literal interpretations. This is why so many tales warn against making pacts with them. A mortal might be granted a wish, only to find the cost is something they never thought to specify, like their firstborn child or all the luck from their family line. This theme reinforces the Fae's alien morality - a deal is a deal, regardless of the emotional or human cost.

- The Teind (The Tithe to Hell): This is a darker and less-known piece of folklore, primarily from Scotland, that adds a terrifying layer to Fae interactions. The "Teind" is a tithe or tax that the Fae are forced to pay to Hell every seven years. The payment? One of their own, or more sinisterly, a stolen mortal. This belief provided a grim explanation for changelings and abductions. It wasn't always for mischief; sometimes, a beautiful human child was stolen to be the payment, sparing a Fae life.

- Liminality as a currency: I mentioned liminal spaces (thresholds, dusk, riverbanks) as gateways to the Otherworld. But in this transactional view, liminality is also the medium of exchange. Fae magic is strongest in these "in-between" places and times because they're outside the normal rules of the human world. It's on a misty morning, at a crossroads, or on Halloween night that a pact can be made, a portal can be opened, or a Fae can cross over. They operate in the cracks of our world because that is where their power is solvent.

(Learn more about Halloween folklore here).

Distinguishing folklore from modern fiction: common misconceptions

Many popular modern ideas about the Fae are products of literature and art that differ significantly from historical folklore.

Physical appearance:

The popular image of the Fae as diminutive, beautiful beings with insect-like wings is a relatively recent invention. William Shakespeare's play A Midsummer Night's Dream was instrumental in miniaturizing Fae in the public imagination.

This trend was solidified during the Victorian era by artists like John Anster Fitzgerald and Richard Dadd, whose paintings depicted intricate fantasy scenes with tiny, winged sprites. And modern stories and sanitised fairy tales often present ethereal, "pure" kinds of fairy characters.

That's not to say the fae in old folklore couldn't be small and beautiful - some groups are described as more beautiful than any human.

But the stories are varied - some are described as (adult) human-sized and have the ability to shape-shift, others more the size of children with a hairy or grotesque appearance, so there is no one-size-fits-all here. A general consensus of folklorists suggests that fae in Celtic folklore are often depicted as the former while the Germanic (or Teutonic) fae are more the latter, though again, there are always exceptions.

In Breton (Celtic) folklore, for example, the Korrigans are described variously as beautiful women who transform and small wrinkled creatures that don't

The real difference is that the romanticized versions of "pretty" fairies, present them generally as "good" while in the authentic folklore, beautiful fairies can be benevolent but are never just "good".

The Seelie and Unseelie courts:

And on that note - the Seelie and Unseelie split or good vs. evil is very much a modern fantasy interpretation. It's not completely without basis but the authentic origin was much less binary:

Seelie from Scots seily, meaning 'blessed' or 'lucky' appears in older ballads like Allison Gross (c. 1783) or in 16th-century witch trials referring to "sillie wychtis." But, it wasn't necessarily describing a specific "good" faction. It was often used as a protective euphemism for all Fae and a way to flatter them. You didn't call them "Seelie" because they were good; you called them that so they might be good to you.

Unseelie is an old Scots word meaning "unholy" or "unfortunate" (usually describing a time or place, like an "unseelie time" to travel), there is very little historical evidence of an organized "Unseelie Court" existing as a counter-weight to the Seelie Court in early folklore. The concept appears to be a later literary invention (likely 19th century or later). In genuine folklore, you didn't have a "bad court"; you just had individual entities who were bad, or "unseelie" times and places where it was dangerous to tread.

Belief in the Fae was a complex and functional system for interpreting the world - as is true of most old folklore stories. Fae folklore provided explanations for natural phenomena, justified social norms (e.g., "stay on the path and be home by dark") and offered a supernatural framework for understanding suffering, illness and death.

While these beings have largely transitioned from genuine folk belief into archetypes for literature and fantasy, their origins are a direct reflection of the historical human experience and our enduring need to explain the unknown.

Article sources

- Briggs, Katharine. An Encyclopedia of Fairies: Hobgoblins, Brownies, Bogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures. New York: Pantheon Books, 1976.

- Campbell, John Gregorson. The Gaelic Otherworld. Edited by Ronald Black. Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2005

- Gregory, Augusta, Lady. Gods and Fighting Men: The Story of the Tuatha De Danaan and of the Fianna of Ireland. London: John Murray, 1904.

- Henderson, Lizanne, and Edward J. Cowan. Scottish Fairy Belief: A History. East Linton: Tuckwell Press, 2001.

- Keightley, Thomas. The Fairy Mythology, Illustrative of the Romance and Superstition of Various Countries. London: H.G. Bohn, 1850.

- Silver, Carole G. Strange and Secret Peoples: Fairies and Victorian Consciousness. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Sikes, Wirt. British Goblins: Welsh Folk-lore, Fairy Mythology, Legends and Traditions. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington, 1880.

- Yeats, W. B., ed. Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry. London: Walter Scott, 1888.

Explore more folklore

Celtic folklore comes from multiple distinct regions and is full of fae - learn more about them all here.

One of the darkest characters in European folklore, this Fae has a variety of old tales that feed into its mythology. Learn more here.

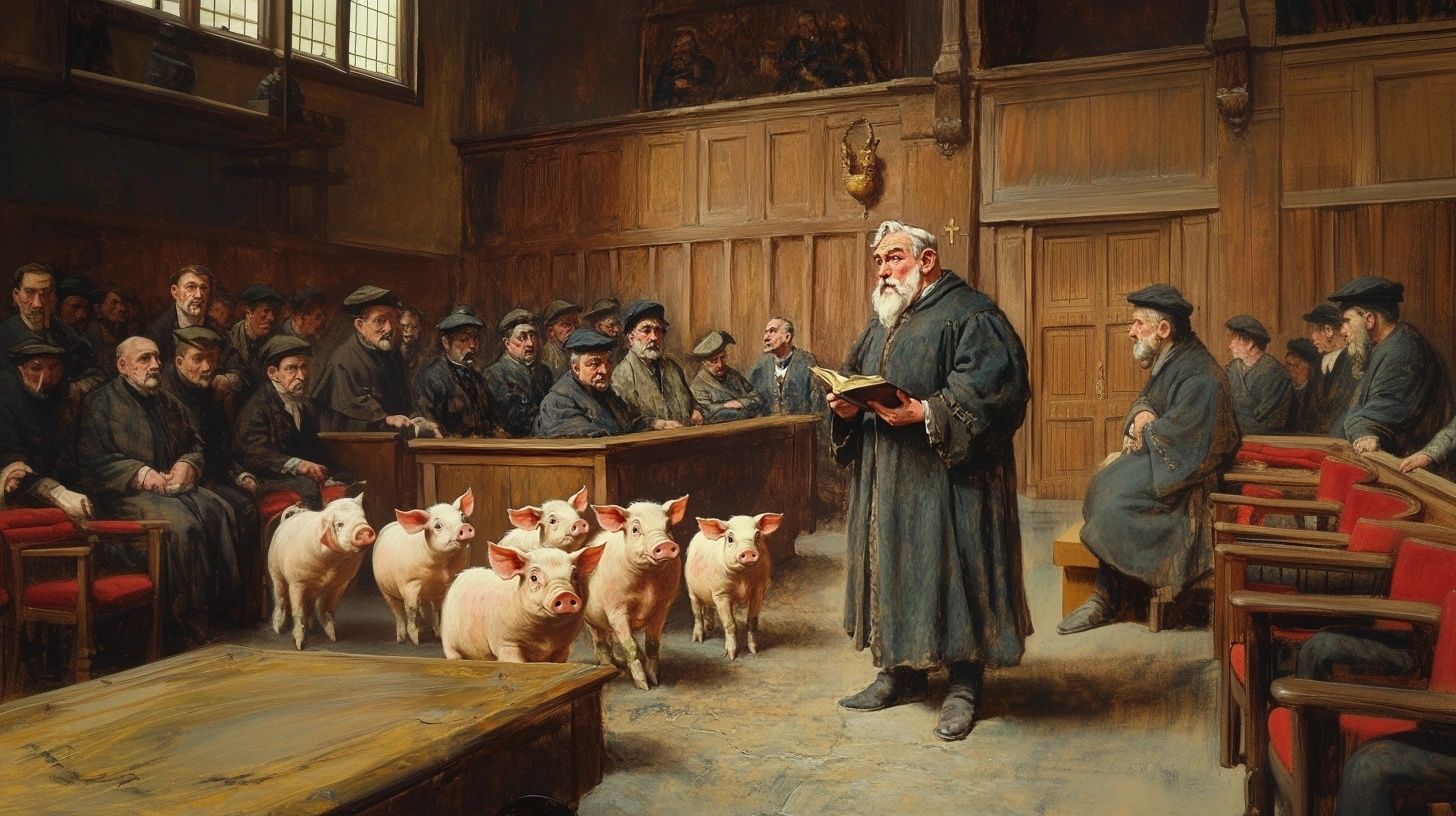

Discover the time when animals were put through real human trials - with lawyers and everything...

From ancient mythology through the witch craze of the Middle Ages and beyond, get an overview of our history with witches here.

Explore US folklore